The journalist and former newspaper editor gives his view on the upcoming coronation of King Charles III

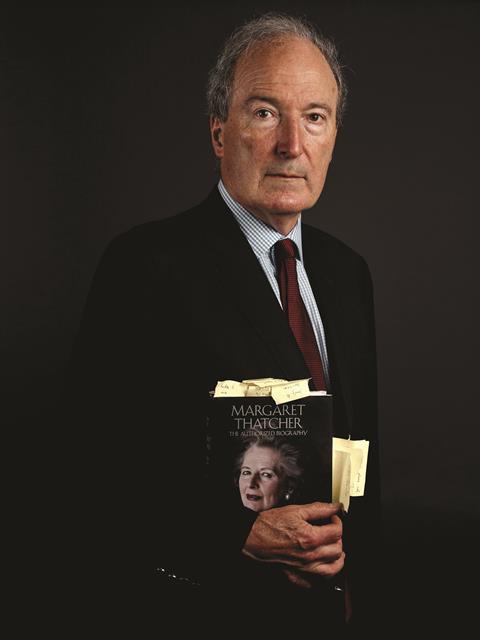

The Eton-educated authorised biographer of Margaret Thatcher, whose full title is Baron Moore of Etchingham, knows his way around the British establishment.

National newspaper editors like Charles Moore are widely regarded as wielding immense power. But Moore says he wasn’t conscious of that during his tenures at The Daily Telegraph (1995-2003), The Sunday Telegraph (1992-95) and The Spectator (1984-90). He was too busy with the day-to-day running of the titles – “it’s amazing how much of your time is consumed with making it the best you can”. He concedes that his position did give him access to the great and the good. “If the editor wants to get hold of someone powerful in any walk of life and find out what’s going on, then he can. It’s a privilege that I didn’t see at the time.”

Moore was a practising Anglican for most of his life, before later turning to Catholicism. He describes the critical moment as recognising that “Christ intended the Church to be universal…so there’s something odd about it being ‘of England’.” The 66-year-old is still “very kindly welcomed” at his local CofE church though, where his wife remains a warden.

Tell me about your family life growing up in Sussex.

It was always traditional that you weren’t supposed to talk about religion or politics, and you can see why, because it makes everyone so angry! But I was not brought up like that. There was a liberal attitude towards discussion – we were a family who loved arguing about ideas.

I used to cause trouble as a child because I went off to friends for tea and started arguing about some public issue in an annoyingly precocious way, which the neighbours didn’t appreciate.

Was there a moment when your Christian faith became your own, and not just something you were raised in?

Yes, but I wouldn’t say a moment, I would say more like a trend.

Except for one or two trivial wobbles that people often have as a teenager, I would say I’ve been a consistently practising Christian all my life. For me, the focus of that was very liturgical. I’m not very good at solitary prayer, I find prayer more efficacious – and this is my fault, not anybody else’s – in a congregation, with a good liturgy.

I was brought up on the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which I always loved. It’s unthinkable now, but all us country people had a bit of the King James Bible read to us every day. We were taught from it in our classes and we had the collects from the Book of Common Prayer at daily assembly, as well as traditional hymns. All that made a deep, favourable impression on me. Even now the phrases come into your mind unbidden and they echo. So I’m a great believer in the importance of children learning words that are unfamiliar to them. I think the idea that you must do something that is ‘relevant’ to the child is wrong. Actually, you should be stretching the mind.

King Charles has a serious commitment to Christianity

Sometimes churches use modern translations of the Bible to make faith more accessible. Why do you think it’s better to stick to the Authorised Version?

There are a couple of reasons. One is that they are great words, and therefore, you muck around with them at your peril. That would also apply to Shakespeare, for example, which can be very hard to understand, but is 100 per cent worth the effort.

But it’s more than that, it is the collective expression of a particular period in history. The English were very religious; they actually understood religious language much better than modern English people do.

One of the fascinating things about religion is that it’s the only way very deep and important ideas can be conveyed to all levels of human intelligence and education. If you talk philosophy to people who are not educated it goes completely over their heads. But you can talk religion to people who are not educated. And the same is true with children. Children are much quicker to pick up ideas about God than they are about economics, let’s say. I think that’s very important.

It’s famously said that the King James version [of the Bible] was “the only good book ever done by committee”. It was extraordinary. It captured a moment when the English knew how to talk about these things.

Of course, one always needs to reinterpret the message in every age. And in that sense, always find new language, but I think it’s been a mistake, as WH Auden put it, to “spit on our luck”. We had that luck, and now we don’t have something we share. And therefore it’s much harder to explain everything.

As a newspaper editor you were in constant competition with rivals, trying to sell more papers than them. It’s often the political personalities, rather than the actual policies, which result in sales, isn’t it?

Yes, and there’s nothing wrong with personality stuff at all. We’re all human beings and we’re interested in other human beings. But I think it’s dangerous when you ignore something that does matter. So for example, I think the Left has tended to ignore the effects of mass immigration, to take a controversial example. And similar accusations can be made against the Right for dismissing the social effects of industrial change. I admit it can be a bit boring to talk about that in a single article.

There’s also a simple question of charitableness. And one of the things I very much dislike about a lot of coverage of the royal family and monarchy is that it’s either at their feet or at their throats – and neither is a satisfactory place to be in. I’m sometimes stunned by how horrible people are about individual members of the royal family. I’ve seen the terrible effects of that in the Charles and Diana fallout in the 1990s, when I was editing The Daily Telegraph. And it’s very bad now in relation to Prince Harry.

THE CORONATION IS ABOUT THE NATURE OF PRIESTHOOD AND ANOINTING

A lot of Christians recognise the incredible Christian faith of the late Queen Elizabeth II, but perhaps have a few more questions about King Charles III. Are they right to be worried?

I would say Queen Elizabeth II was the greatest Christian monarch in known history. I’m not saying she was a saint, although if we were a Catholic country I wouldn’t be surprised if she was made one! There was this air of calm about her – she lived a sort of prayerful, simple Christian life.

But I think the criticism of the new king is not very fair. Obviously, he got into very severe marital difficulties and that’s acknowledged, but I think in terms of his commitment to the Church of England and to spiritual matters, to the duty which his mother also felt, to his way of being kind to all denominations and all faiths, I think those are things he cares about very deeply. He has a serious interest in Christianity – he’s a churchgoer, a lover of liturgy – and [has] a serious and kindly interest in other faiths.

But isn’t that interest in other faiths one of the ways in which he is different? In some of her Christmas speeches, the late Queen emphasised her own personal faith in Jesus Christ. King Charles may talk about the importance of interfaith relations, but he doesn’t speak about his own personal Christian faith in the same way as his mother, does he?

Well, I’m not sure you’re quite right about that. I must be one of the few people who have read all of her Christmas messages. They are definitely Christian, and explicitly so, but it wouldn’t be true to say that they express her personal faith directly. She never did what you might call an ‘evangelical thing’ – “God came into my life…” She always kept a reserve about that, because I think she knew she shouldn’t be imposing her Christianity on other people. What she wanted to do was to show the importance of living in that way and learning from the Christian example.

How prominent a role will the Christian faith play in the coronation?

I think you’ll see at the coronation that there’s no compromise with the specifically Christian elements, which are overwhelming. It’s the most Christian of all the services connected with the royal family, and it includes the communion. But I think we will see a greater reflection of the multifaith society that we are today. I think that’s the right combination.

How do you think wider society will react to the explicitly Christian elements of what is taking place?

There will be a significant number of people watching it who will not have the faintest idea what this is about. I often find that in public even if you mention “the ten commandments” or “the good Samaritan” people don’t know what you’re talking about.

The coronation is not just about God. It’s about the nature of priesthood and anointing and how the king’s role is made sacred and how that derives from what happened to King David. So it goes a long way into areas that a lot of people find obscure. But I would be very surprised if people find that upsetting. I think the overall feeling they will get is of continuity, seriousness, commitment and service, and something deep and universal which is expressed in kingship.

People sometimes misrepresent this as ‘the divine right of kings’. That’s not the case. It’s about the divine duty of kings. The grandest person is the greatest servant. One of the Pope’s titles, of course, is servus servorum Dei, servant of the servants of God. So it’s this paradoxical, Judeo-Christian idea that the highest ought to be the lowest.

I’VE BEEN A PRACTISING CHRISTIAN ALL MY LIFE

You’ve rubbed shoulders with some contentious political figures – not only were you asked to be Margaret Thatcher’s biographer, but when you were at The Telegraph in the 1980s you employed a young journalist by the name of Boris Johnson, who later gave you a life peerage…

Yes, we were close colleagues. The essential thing about Boris – a very obvious point, but somehow people miss it – is that he has very grave defects which are never going to go away, but he’s very, very remarkable. And in my view, that meant he was the only person who could pull off Brexit, which I supported. He succeeded in the referendum, then in becoming the party leader, then in getting Brexit done (even if in imperfect form) and then in winning the general election. Those are remarkable achievements, and only he could have done that. Then things went wrong, and I still haven’t been able to work out how much of that is to do with the bad luck of Covid, and how much is to do with Boris’ personal failings. Clearly, both are involved.

It’s a bit more than “personal failings”, isn’t it? From a Christian point of view especially, wasn’t there a huge integrity issue with Boris Johnson? And shouldn’t society expect politicians to operate with a basic standard of morality, and hold them to account when they don’t?

Nobody could say that Boris was a perfect human being. But what I think is missing is how much all politicians (and they can hardly avoid it) do quite bad things and don’t tell the truth. So the idea that this [untruthfulness] is a thing that Boris introduced into politics, and was unknown before, is very far from the case. I’m afraid it’s a quality of some very remarkable leaders who have gone before. So Boris stands in the tradition of Disraeli and Lloyd George, both of whom were absolutely outstanding politicians, but were not scrupulous.

To hear the full interview, listen to Premier Christian Radio at 8pm on 29 April or download ‘The Profile’ podcast

No comments yet