Skye Jethani explains why digital technology is disrupting our 500-year-old emphasis on lengthy Sunday sermons

I am a preacher. For hundreds of years my craft was in high demand. People travelled inconvenient distances to hear my sermons, they paid for my training so I could improve my skill, and they sacrificed to supply me time and space to study and write my weekly monologues.

But now the forces of modernity and technology have conspired against me. Seemingly overnight the conditions that made my vocation valuable have disappeared. I feel like a lamplighter at the dawn of the 20th Century, watching the cold glow of Edison’s lights replace the warm flicker of flames across my city. People still need light, just not mine.

I’ve been wrestling with the changing nature of preaching ministry and the local church in recent years. What concerns me, however, is that many of my pastoral peers are not. Church leaders have largely ignored the monumental changes underway caused by technology. Perhaps it’s because we’ve forgotten our history. Every major advance in communication technology has triggered a corresponding change in church structure and worship. Two thousand years ago, communication was advanced by Rome’s efficient roads, which allowed the message of Jesus and his apostles to quickly spread throughout the world. Within decades, the Church went from a small sect of Jews in Galilee to a multicultural movement reaching from Spain to India. One could argue that without Roman roads, the Christian faith could not have flourished.

1,500 years ago, the codex (aka the book) replaced the scroll as the preferred technology for written communication. Books allowed large amounts of information to be efficiently stored, studied and transmitted. There’s a reason most scrolls never exceeded 20 sheets in length. It was extremely difficult – and costly – to find a specific point in a rolled document, as text could only be written on one side. Books overcame these shortcomings and brought unity to the Church’s teachings with the canonisation of scripture. They also triggered the growth of monastic communities, as books were easier to carry into remote regions.

Reversing supply and demand

Five hundred years ago, Gutenberg’s printing press allowed information to be copied and shared at unprecedented speeds. For the first time, the Bible was accessible to the masses, and in their own languages. Without the printing press, the Protestant Reformation, like most attempts at reform before Martin Luther, would have been a brief, local affair, rather than a world-changing movement. The translation and transmission of the Bible also revolutionised the way many Christians worshiped.

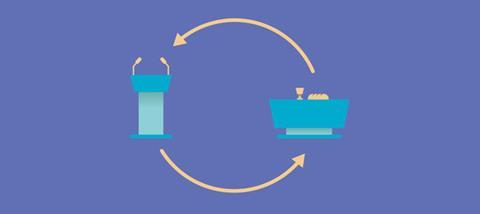

Thanks to the printing press, and the Reformation it facilitated, demand for Bible teaching exploded. The supply of Bible teaching, however, remained scarce. Until relatively recently, few people were literate enough to understand and communicate scripture’s content. This high demand/low supply gave rise to the familiar form of Protestant worship many of us still experience today. Christians handed a Bible to the most educated person in town, and they gathered every week to hear him teach from it. Five hundred years ago, the printing press was instrumental in shifting the focus of Christian worship from the bread and the cup to the sermon and the preacher; from God’s presence at the table to God’s presence in the word.

A dramatic restructuring of the Church's worship is likely to be on the horizon

There have been remarkable advances in communication technology since then – the telegraph, radio and television come to mind– but none managed to change this high demand and low supply of Bible teaching that fuelled sermon-centric Protestant worship – until now.

With the advent of digital technology and smartphones, we are witnessing the most significant shift in communication since the printing press – just ask anyone in the music, publishing or journalism industries. The full implications are still uncertain, but if the pattern of history continues, a dramatic restructuring of the Church’s worship is likely to be on the horizon. In fact, we are already seeing the shift, as the supply/demand equation for Bible teaching has reversed.

With increasing pluralism and secularisation in many Western societies, demand for Bible teaching has declined significantly. Simultaneously, there exists a massive oversupply of Bible teaching via apps, podcasts, videos and websites. This inversion of supply and demand means the economic assumption that has sustained Protestant church attendance and sermon-centric worship for 500 years no longer exists.

In the past, access to Bible teaching required gathering with others in a sacred space at a set time to passively listen to a trained orator explain the scriptures. The ubiquity of this model causes us to overlook how inefficient and expensive it is. Significant cost is required for the physical spaces (church buildings),the training of clergy (theological colleges) and the writing of sermons (professional pastors). To cover these expenses, Christians were expected to sacrifice their time and treasure by committing their households and tithes to a single local church. This expectation was tolerated because, like any other commodity in high demand and in low supply, the market demanded it. This has been the economic assumption supporting most Protestant churches for centuries.

Today, however, those seeking Bible instruction have an almost infinite supply of immediately accessible and inexpensive options. Anyone with a smartphone may access thousands of sermons from anywhere, anytime. The problem is no longer access to Bible teaching, it’s curating and navigating the right Bible teaching. This low demand and high supply means the market for Bible instruction has reduced the cost to virtually zero. That’s great news for Christians seeking excellent Bible teaching, but not for church leaders trying to keep their pews and plates full on Sunday.

Most institutional churches continue to make the preaching act the centrepiece of Sunday worship, and Sunday worship is the centrepiece of most church ministries. An audit of virtually any Protestant church will reveal a massive percentage of the institution’s resources (space, funds, leadership) are devoted to the Sunday preaching event and its related activities. In other words, most churches have inherited a 16thCentury model that is increasingly unsustainable with 21st Century realities.

Changing the discipleship model

I talk with Christians regularly –particularly millennials, for whom digital content is native – who ask me why Sunday morning church attendance is important. They don’t recognise the value of a large group gathering built around a 35-minute Bible lesson when they have access to (often superior) sermons 24/7 via their smartphones. I also speak with church leaders regularly – particularly those dedicated to the centrality of preaching – who express frustration over declining attendance and commitment-averse millennials. I trust you can see the dilemma already. Pastors carry a Reformation mindset that sees Bible teaching as a scarcity, which makes their sermons valuable, while millennials with a digital mindset recognise the abundance of Bible teaching available, making most pastor’s sermons, and therefore Sunday attendance, unnecessary.

Most Christians aren't getting their Bible teaching primarily through Sunday sermons anymore

Church leaders face two options. Either battle the marketplace currents and strive to convince enough people to pay for sermon-centric Sunday gatherings, or rethink that model to better fit the realities of making disciples in the 21st Century. It’s worth remembering that the Protestant Reformers’ goal was not to rethink the church’s worship. Their goal was to make disciples of Jesus. In the 16th Century, emerging technologies provided new tools to accomplish this task. These new tools eventually changed how church leaders functioned and how the church worshiped. Their experience provides an important lesson for us. Our goal remains the same – to make disciples of Jesus. Biblical instruction also remains an indispensable part of that goal. After all, Jesus said making disciples meant “teaching them to observe all that I have commanded” (Matthew 28:20, ESV). Scripture also says: “Let us consider how to stir up one another to love and good works, not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another”(Hebrews 10:24-25, ESV). We should not abandon incarnate gatherings for ‘digital church’ or synthetic communities found on social media. Therefore, both biblical instruction and gathering with believers remains essential to our faith and mission. But with the advent of new tools and new technology, we must ask ourselves two questions. Firstly: “What is the best way for growing disciples to engage with the biblical teaching we need?” And, secondly: “What is the best way for disciples to find encouragement and be equipped for good works when we gather?”

Just as these two questions have been answered differently in different centuries, they will also be answered differently in diverse contexts, settings and cultures today. What is effective and acceptable in a developed Western city such as London may be entirely unlike what works in rural India. Nonetheless, let me attempt to engage with these two questions based upon my own context living and ministering in the USA. The United States remains a very religious country, but church attendance has been declining for decades. Research by the Barna Group found that even very committed Christians only attend church twice per month on average. (Thirty years ago the average was twice per week.) Other data suggests Christians in the US have their beliefs shaped far more by their media consumption than by their church’s teaching. According to data by Nielsen, the average adult in the US spends more than ten hours per day connected to media. These findings made me seriously question the value of spending half of my week crafting a Sunday sermon. Why was I pouring so many resources into a 30-minute sermon hoping to influence church members, while ignoring the 73 hours of media they were engaging with outside the church? Hearing a doctrinally sound sermon twice per month is no match for marinating in heresy for hours every day. To be fair, religious media isn’t all prosperity preachers and Christian nationalism. There is a lot of excellent, orthodox content available online – but few churches are helping their people find and engage with it. What if church leaders reallocated some of the time that had been devoted to sermon preparation, and instead used it to curate the best online biblical resources and content for their people to engage with, Monday through Saturday? That will only happen if we accept that discipleship doesn’t only take place on Sunday mornings, and admit that most Christians aren’t getting their Bible teaching primarily through Sunday sermons any more. These facts may not be very satisfying to a preacher’s ego, but as American businessman and writer Max De Pree famously said: “The first responsibility of a leader is to define reality.”

Coming back around the table

If we no longer make preaching the centrepiece of Sunday worship, what ought to replace it? The answer will depend on a church’s particular context. One option, which is growing among evangelical churches, is the rediscovery of the Lord’s table. By making the bread and wine the focus of worship, some churches are avoiding the pitfalls of a personality-centred culture that often results from sermon-centred worship.

Glenn Packiam, a worship leader and associate pastor at New Life Church in Colorado, experienced the fragility of preacher-centred worship in 2006 when the church’s senior pastor was embroiled in a national scandal. “As a large church with a prominent pastor,” he wrote, “we were prone to focusing on one individual.” After the scandal, Packiam said: “We needed something else to help us centre the focus of our worship services on Jesus.” New Life Church began to incorporate the Lord’s table into their weekly gatherings.

Packiam says New Life still values singing and Bible teaching: “But here’s the thing about the music and the preaching: they rely heavily on the human element. An unskilled musician could ruin the moment; a vain preacher could steal the attention...both music and rhetoric are prone to manipulation.” Communion is different. “The table was the place where Christ alone was the focus.”

The Eucharist has another advantage over sermons – it can’t be digitised. Communion is an incarnate experience. The bread is held, blessed, broken, given and eaten. Believers gather to pray, confess, absolve and affirm. The entire enterprise requires engagement and activity. It cannot be passively listened to via headphones. The body and blood cannot be downloaded or streamed.

Other congregations are using the time once dedicated to sermons for more meaningful communion with one another. Recent data suggests there is an epidemic of loneliness in both the US and UK. We are more connected than ever digitally, but more isolated than ever relationally. Attending a church with hundreds of others, all facing a stage and listening to a preacher, does little to overcome this sense of disconnection.

Francis Chan founded and led a megachurch in California for many years before abruptly leaving it in 2010. Three years later, he launched a network of house churches in San Francisco. Bible teaching is done primarily via online videos members engage with during the week, which allows the church gatherings to focus on prayer, fellowship, practical application, relationship-building and encouragement. It also means the pastors and elders of the home groups can give more attention to care and discipleship than preparing sermons each week. Similar models are being tried in many other post-Christian, urban areas where the traditional model of large gatherings for Bible lectures are simply economically unfeasible.

These are just examples of what’s possible when church leaders open themselves to reconsidering sermon-centric worship. I’m not advocating one new model. Heaven knows, every ecclesiastical structure has its benefits and weaknesses. But I do think we need to be asking new questions, given the new tools now available to us. The greatest barrier to this work, however, is not the inertia of tradition or the time necessary to learn new strategies. I suspect the most significant obstacle is within preachers’ hearts. Are we willing to give up the spotlight? Are we willing to step aside from the pulpit and welcome other gifted Bible teachers into our ministries? And are we willing to lay down our lives, our microphones and our egos for our sheep? The future shape of the Church depends on how we answer these questions.