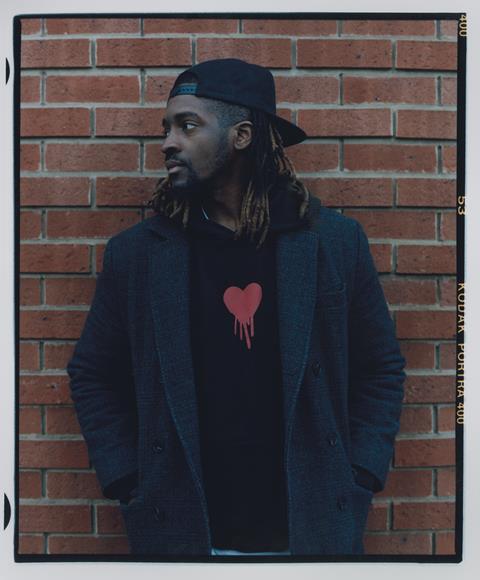

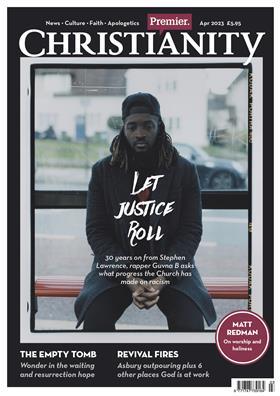

On the 30th anniversary of Stephen Lawrence’s murder, award-winning Christian artist Guvna B asks: how much progress has society and the Church made when it comes to racial justice?

In 2017 I sadly lost my dad to cancer, and it turned my world upside down.

He had moved from Ghana to London with my mum in their early 20s in search of new opportunities. He wanted to work, not just hard, but smart, and provide the best life possible for our family.

On the London council estate where I grew up, our story wasn’t unique. Working-class Africans, Asians, Caribbeans, Europeans, South Americans and, of course, the native British, all wanted the same. The beautiful thing was that even though we looked different, the melting pot of all our differences united us.

A few weeks after my dad’s death I discovered he had left me some money. I was surprised because, for the most part, my family just managed to keep our heads above water; we were rarely in surplus. I suppose his gift was a testament to just how hard he worked and how important it was for him to secure our future. The money contributed to the deposit my wife and I put down on our first property.

Filled with excitement, a week before we moved, I went down a rabbit hole on the internet. I wanted to know more about the south-east London street we would soon call home. What I found stopped me in my tracks. The most famous person that had lived there was one of the suspected murderers of 18-year-old Stephen Lawrence. He was one of the five men arrested over the racially motivated attack in 1993 that sent shockwaves through the nation.

Murder

Just like my mum and dad, Stephen’s parents had emigrated from their home country – not Ghana but Jamaica – and they too were in search of opportunity. There’s often a misconception that by “opportunity”, immigrants actually mean “handouts”. They don’t. Mass migration from the Caribbean (on the likes of HMT Empire Windrush) was driven by the need for workers to help rebuild England after the second world war.

It was supposed to be mutually beneficial. But it’s one thing for immigrants to realise they might not be as welcome as they first thought, it’s a whole other thing to realise their children are not safe on the streets. That was Doreen and Neville Lawrence’s story. Their son, Stephen, was slain by a gang of white thugs because of his skin colour. They treated him as though he didn’t belong.

In the aftermath of his murder, the Churches Commission for Racial Justice (CCRJ) got behind the campaign to bring Stephen’s killers to justice, by not only marching peacefully through the streets of London as a form of protest, but by putting their tithes where their mouths were and providing financial support for the Lawrences’ privately funded campaign.

This campaign resulted in an inquiry in 1997 and, in 1999, the Macpherson report was published, a ground-breaking 350-page document that branded the police force institutionally racist and, eventually, in 2012, helped bring two of Stephen’s killers to justice. While the CCRJ played its part, a large majority of the wider Church left much to be desired. From speaking to friends and Christians who were a lot older than I was in 1993, I understand that although there were some churches who supported the Lawrences and called for policy change, a large number didn’t view the case as enough of a priority.

With more than 40,000 registered churches in the UK, justice is unlikely to roll like a mighty river (see Amos 5:24) if only a small portion of that number engage. I was only four years old when Stephen was killed, but I remember being left hurt and disappointed by my own church’s passivity towards George Floyd’s murder 27 years later. On the Sunday that followed his death, a mention, a prayer, a public sign that they cared would have sufficed…But there was nothing.

My attack

Even though it was an uncomfortable feeling to move to the road where one of Stephen’s suspected killers had lived, the reason I eventually felt peace was because, as a society, we have moved forward in the area of racial justice.

In 2022 the Church of England, for example, publicly accepted responsibility and apologised for the part that it played in the slave trade. This is a conversation that had previously been swept under the carpet (CofE money produced from the slave trade helped pay the incomes of poor clergy in the 18th century). Justin Welby said he was deeply sorry and, earlier this year, introduced a fund “to address past wrongs”. In the light of these milestones and the importance of George Floyd’s life and death in opening society’s eyes to racism, I figured that what had happened to Stephen was unlikely to happen to me – or so I thought.

One of the men proceeded to throw hot coffee in my face followed by a punch

On 24 August 2021 I went to get a coffee in my local area. As I left the coffee shop and approached my car, there were three white men standing in front of it. I said: “Excuse me, please,” but they acted as if they couldn’t hear me. I asked once more and they ignored me again, so I gently brushed past them. One of the men proceeded to throw hot coffee in my face followed by a punch. This all happened within a five-minute drive from where Stephen Lawrence was murdered.

I called the police. When they arrived at the scene, the three men had made a run for it and I was there alone. One of the first questions the officers asked me was if I had been in trouble with the police before. A strange question to lead with, considering I was the one calling for help. I’m not sure what relevance that question held, or whether it would have been asked of an elderly victim of an attack, or a white middle-class woman.

Another question they asked me was whether the perpetrators said anything racist. I realised in that moment that maybe we haven’t made the great strides in society that we think we have. The perpetrators didn’t say the “N” word, but that doesn’t mean their actions weren’t racially motivated. People may have learned what not to say, but it doesn’t mean they’ve changed their prejudices.

1 Samuel 16 says that man looks “at the outward appearance” but God “looks at the heart”, and I wonder if that is what we as a Church need to really grab hold of in this season. In a time where church staff and volunteer teams are getting more diverse, and Black people are treated a little more equally, we must ensure we don’t enter the realm of learning how to behave and how to tick boxes, without changing our hearts.

Corporate responsibility

I grew up in a majority Black Pentecostal church in east London, led by a Ghanaian pastor. It felt like an extension of what it was like inside my home. Soulful and energetic praise and worship music, great African food after services, powerful sermons and a room filled with people that looked like my family. We felt at home and like we belonged. But even though our church was many amazing things, one thing it wasn’t was diverse.

In my late teens, I wanted to find faith for myself – not one lived vicariously through my parents – so I started to search for a church of my own, and I happened to stumble across one that I really liked in the heart of London, which happened to be a majority white church.

The community aspect was amazing. The church attracted people from many different walks of life and a lot of students, which I quite liked because I was at a similar stage of life. I felt I belonged, and I enjoyed being exposed to a different expression of worship and a different way to do church.

Assuming a leadership position doesn’t put an end to racism, but a seat at the table sends the message that your voice is valid

A few years later, the church started to plant locations in inner-city areas that contained a breadth of nationalities. As a result, it became more racially diverse, but interestingly, it stayed extremely white at leadership and board level. Black leaders were deployed to look after the new locations, but they were more like puppets than pastors. All strategy and messaging was passed down from the top, and the Black leaders were mainly there to distribute it to their diverse communities.

In his book, We Need to Talk About Race (SPCK), Ben Lindsay describes this phenomenon as “the Guinness effect”: white majority leadership at the top, and Black majority congregation below. Although assuming a leadership position doesn’t put an end to racism, a seat at the table sends the message that your voice is valid, that we want to hear you, and that you belong here. That church has since made real efforts to find more of a balance from the top down and I’ve spoken to many pastors who openly admit they have work to do in this area also.

While we’re on the subject of balance and belonging, a pastor friend of mine was leading a church just outside London when God spoke to him and said the church was currently for the wealthy and the white. “It needs to be a church for everyone”, God said, so my friend strategically made the youth group more outreach-focused. He started to attract young people from a different background, class, nationality and economic status.

IF THERE ARE BLACK PEOPLE IN OUR CONGREGATIONS WHO FEEL THEY AREN’T WELCOME, WE NEED TO ASK WHY

Some of these young people had issues from childhood they were working through, some were vulnerable and some thriving, but they all found a home at this church. God was moving in a powerful way – but then my friend started to get emails from the white, wealthy people in his congregation who had been there a while. One family after another said they were leaving the church. When he asked why, they said they didn’t like the direction it was going in. In other words, they didn’t want to mix with those who weren’t like them.

Guvna B’s recommended resources on race

1. We Need to Talk About Race - Ben Lindsay (SPCK)

“Delivered with a perfect balance of truth and grace, this book will open the eyes of many. As a young black man navigating a predominantly white world, this book is a timely weapon of wisdom and a game-changer.” – Guvna B

2. Brit(ish) - Afua Hirsch (Vintage)

You’re British. Your parents are British. So why do people keep asking where you’re from? This book looks at race, identity and belonging in modern Britain.

3. The Mixed-Race Experience - Natalie and Naomi Evans (Square Peg)

An exploration of what it’s like to grow up as a multi-racial person in a white-majority area, from the founders of the anti-racism platform

4. Jesus and the Disinherited - Howard Thurman (Beacon Press)

Famously known as the text that Martin Luther King Jr sought inspiration from in the days leading up to the Montgomery bus boycott, this book argues that Jesus is a partner in the pain of the oppressed.

5. Bridgeland Road ft Michaela Coel Guvna B

You’ve read the story, now experience the song that recounts more of the details of my racist attack.

LOVE ONE ANOTHER

Stephen Lawrence was treated as though he didn’t belong, and the repercussions of that were catastrophic. I’d like to think the Church has made promising strides in the area of racial justice, but if there are Black people in our congregations who feel they aren’t welcome, we need to ask why that is, and what needs to change.

Before George Floyd there was Stephen Lawrence and countless others. Thirty years on from Stephen’s murder, I can’t help but ask: have attitudes towards race really changed – in wider society or in the Church? I travel to a lot of churches up and down the country to play music and speak to young people and, from what I’ve seen and heard, churches are not only becoming more diverse from the top down, but they’re also thinking more about the experiences of their Black members and how they can build bridges. But the reason we can’t rest on our laurels is because there is still a lot of work to do.

I believe Christians are some of the best at helping those in need. The church I am a part of now (who incidentally also have work to do in the area of race) launched the Love Your Neighbour Campaign (loveyourneighbour.uk) a couple of years ago, which many churches across the nation have become a part of. It has united the Church beautifully and provided more than 1 million meals a month to those in need. It’s incredible, but I think God is calling us to more.

Handouts can feel great because they make us feel important, but do you know what’s more costly? The Church giving up some of its wealth, its comfort, its positioning and leaving the four walls of the building to get its hands dirty. Partnering, collaborating and building relationships with organisations and communities who are actively fighting against issues like racism is a start. We have to begin treating those we help like people, and not projects. When we start to do this, we tend to focus less on political or denominational agendas, and more on love and empathy.

Whether it’s the life-ending racist attack on Stephen Lawrence, the slow nine-minute murder of George Floyd, or the eye-opening attack on me in broad daylight, the thread that holds these three completely different events together is an attitude of hate. The antidote for that is love, something Jesus intended for the Church to have in abundance. The mandate is clear: “A new commandment I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another” (John 13:34-35).

This article forms the cover story for the April 2023 issue of Premier Christianity. Subscribe today

No comments yet