It is 20 years since Rev Inderjit Bhogal OBE launched the first City of Sanctuary in his home town of Sheffield. But the work of welcome, hospitality and reconciliation is more vital now than ever, he says

Inderjit Bhogal was raised a Sikh, but when he and his family moved to England in the 1960s, there were just two Sikh temples in the whole country – and none near his home in Dudley. With no prospect of being able to attend a gurdwara, he instead found the nearest place of worship, which happened to be a Methodist chapel. The church made him “feel really welcome” – a stark contrast to the racism he experienced from other parts of British society at the time. He started attending regularly, becoming “captivated by the story of Christ” in the process, and ultimately converting to Christianity.

What stood out most to Bhogal was Jesus’ love for those on the margins: “He spent most of his time with those rejected by others, the most excluded,” explains Bhogal, quoting Matthew 25 to explain Christ’s expectation that his followers should support “the least of these brothers and sisters of mine” (v40). It would impact his Christian faith profoundly.

Bhogal says it’s obvious whom our modern society deems the least important. “Who is the most unwanted? It’s the refugees,” he says, fleeing danger yet often feared as ‘other’ by those who understand little of where they come from or what they have endured.

A trickle, not a flood

Ninety per cent of the world’s 100 million refugees come from countries in or close to conflict. Bhogal explains that the majority of those forced to leave their homes are trapped in their own country or seek sanctuary in a neighbouring one. A “very small proportion” take great risks to venture further into Europe and “a trickle” attempt the treacherous journey to the UK on “useless little boats, because they don’t have a safe route to get here”.

Bhogal is highly critical of the language of “invasion” used by politicians such as former home secretary Suella Braverman. “People from Ukraine came here on airplanes. Nobody said: ‘Oh, we can’t take any more refugees.’ But when they come from Asia or Africa, we’re full. And if you come here, we will detain you and deport you to Rwanda. That’s where my passion for justice comes from.”

Providing sanctuary for those most in need is: “the most repeated, ethical requirement of God,” Bhogal says “and therefore part of our prophetic witness”. But what does this look like practically? Bhogal is the founder of City of Sanctuary UK – a network that encourages inclusivity, solidarity and compassion for people from a forced displacement background. The first City of Sanctuary was established in 2007, and there are now more than 100 towns, villages and boroughs that have signed up to provide support to refugees and people seeking sanctuary. The programme has expanded to include schools, libraries, universities, football clubs, theatres and even a maternity ward. Naturally, many churches have also signed up, although Bhogal would like to see more. To this end, he is working with Churches Together in Great Britain and Ireland to help places of faith better understand why a scriptural response is needed to a situation that many see as purely political.

“What’s the big item on the news every day? It is small boats, refugees.” The government’s strategy is clear, he says: the “hostile environment”, originally pioneered by Theresa May, now includes the contentious Rwanda Plan. It aims to make the UK less welcoming to those seeking asylum. In response, the Church must “challenge hostility with hospitality”, responding to the scriptural command to “love your neighbour as yourself” (Matthew 22:39).

As Bhogal’s own experience proves, many churches are already doing this, welcoming and supporting those seeking sanctuary, including refugees. This, says Bhogal, is how the Church demonstrates that it can offer “a still more excellent way” (1 Corinthians 12:31) to the discord and fear that so often prevails.

Pursuing peace

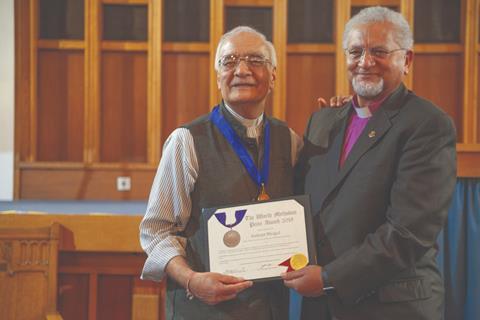

Mistrust between communities is high – especially since the 7 October attack by Hamas on Israel, and the subsequent Gaza war. But the Methodist world peace prize-winner believes divisions such as those we’re seeing today between Jews and Muslims often come from a lack of relationship and understanding.

While there are no easy answers to solving the issues in the Middle East or the crisis in South Sudan, Bhogal has spent his life seeking nonviolent answers. “I think war and violence – whether it’s with weapons or words, whether it’s domestic, in personal relationships, congregations or among neighbours, or internationally – you have to look at nonviolent ways to resolve it. Resolving conflict through dialogue is not a “soft option”, he stresses.

Dialogue is not about dilution

Bhogal started his first inter-faith group aged 20, to bring together Muslims and Christians following Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1991. The Cold War had ended, but the Gulf War gave the West a new enemy in the form of Islam, he says. What started with three Christians and three Muslims meeting together soon expanded to include all faiths.

Unlike some in the inter-faith space, Bhogal is upfront about the exclusive claims of the Christian faith. He’s undertaken costly trips to Amritsar, India to meet with Sikh supreme leaders. Each time, he plainly asks them what they think of Jesus’ declaration that: “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6). “Dialogue is not about dilution. It’s not about all being the same,” he explains. “If we’re all the same, there’s nothing to talk about.”

But neither should Christians fear those who believe different things to us. “If you look at scripture, whenever an angel of God appears, invariably they begin with the same sentence: ‘Do not be afraid.’ So I want to say: ‘Don’t be afraid of those who are different from you.’ How do you dispel fear? By building mutual respect, understanding and trust.

“It’s not about eroding difference or assimilating everybody. We’re all made in the image of God. We’re one, equal but not the same. If we could model that in our world of conflict it would be a great witness.”

No comments yet