We’re twelve years on from ‘Bellgate’ - the furore over the release of Rob Bell’s controversial book on heaven and hell. But Chine McDonald says the questions raised by that episode are more pertinent than ever

February marks twelve years since ‘Bellgate’. For those who were not glued to Christian Twitter in February 2011, this was the furore over the release of post-evangelical pastor Rob Bell’s book Love Wins (HarperCollins).

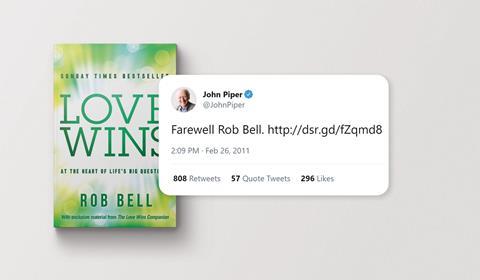

Loved by some, the book drew heavy criticism from others who strongly disagreed with Bell’s universalist understandings of heaven and hell. In response to a video in which Bell outlined the key messages in Love Wins, elder statesman of conservative evangelicalism, John Piper, tweeted the now-famous line: “Farewell, Rob Bell.” He was cancelling Bell, calling him out as a heretic.

Like many of the controversies within the Church over the centuries, Christians divided along two distinct and opposing lines. You were either on Piper’s side or Bell’s.

In recent years, there are many examples of how polarised our society has become, often exacerbated by social media. Increasingly, we are living, loving and worshipping alongside those who think the same as we do, politically, socially and theologically. Where there is difference of thought, there is often tension, fracture and relationship breakdown. It feels safer to only interact with those who are like-minded.

I’m ashamed to admit that in the weeks following the Brexit referendum, I unfriended two people from social media. I just could not bear to hear people being so vocal about a view I could not comprehend. I didn’t want to understand their point of view, I just wanted to remain in my echo chamber. Perhaps it was a coping mechanism; a way for me to reduce the rage I felt.

There are many examples of topics on which views are so strongly held that they become identity issues: Leaver or Remainer, Tory or Labour, anti-vaxxer or anti-anti-vaxxer. Sadly, the Church replicates these divisions and adds its own. We divide along theologically conservative or liberal lines. We have vicious public debates on sexuality and gender.

Having worked for Christian organisations across the spectrum, I’ve seen the venomous tone in which these debates play out up close and personal. I’ve heard the way we speak about those with opposing views when they are not in the room.

But I also have the privilege of deep friendships with those with whom I completely disagree. I can’t think of a public friendship among leading Christians whose beliefs differ, however. Wouldn’t it be great to see Piper and Bell sharing a selfie of themselves having a meal together, perhaps discussing heaven and hell and posting that on Twitter?

Relationship is the key: as Amanda Ripley writes in High Conflict (Simon & Schuster), being in relationship with someone with whom you disagree doesn’t mean you have to change your opinion: “We will continue to disagree about many things. But usually, relationships make it harder to dismiss and dehumanise other people.”

I think there is a lesson for all of us in reaching across the divide. When encountering those with whom we disagree, maybe we should say hello rather than farewell.

2 Readers' comments