I have religious sympathy with people. I was brought up very religiously. My dad was a lay preacher, my great-grandad was a Baptist, nonconformist preacher, my sister is a vicar in the Church of England. I was brought up in that culture. We always went to church every Sunday, and it was fairly full-on. The first gigs I did were in the Wesleyan church in Clapham Junction. They believed you had to encourage people to get out and spread the word, so they’d get kids up in the pulpit reading poems or telling stories. So, at the age of four I did my first gig, reading an AA Milne poem from the pulpit. When I was eight, I could sing the books of the Bible. I probably could remember some of them now. I love the language and I like the stories and all those songs that I grew up with. The whole thing of the Church and faith just peeled away. I declared myself an atheist when I was about eight or nine. So I am very much at home with this stuff. Salman Rushdie, in one of his books, describes a character as having a hole in his stomach where his faith used to be. And I kind of know that feeling. I’m an atheist to my core – but there’s part of me that has this deep longing to go back to that time when I could believe, when there were certainties, and to all of the things that I grew up with: when the emotional fabric and the language and the culture was intact. I suppose the lack of empirical proof for religion was key to losing my faith. But there was also a sense of: ‘This is nuts, none of it makes sense.’ The people I was hanging out with were very reactionary types. My dad was quite a reactionary fellow. My grandad was, too. So their religious faith was very much about them being right and everyone else being wrong. I remember my step-grandad trying to convince me that Catholics weren’t the same as us. And even at the age of seven you just go: ‘What? What do you mean they’re not the same as us?’ Because it’s stupid. I still go to church. I go at Christmas. I love carol services. I love singing in groups. And if you’re not in a choir or you’re not a football fan, the only chance you get to sing in groups is at church. And there is something lovely about it. This is the fabric which we lose with our religion when it just crumbles around us. I like the fact that there’s quite a lot of religion that’s about social justice. That’s important. I’m comfortable working with people of faith when they use their faith in a positive and just way. I’d rather have a Christian Socialist than an atheist capitalist. I look at it that way. I like the fact that our lives get complex and we see the deeper complexities within each other, and that we understand that just because we don’t agree with each other, doesn’t mean that we can’t work together on the fundamental stuff. The important stuff. And what we do is what’s important. So the fact that someone chooses to believe in God is incidental. If they want to get out on a picket line, or if they want to get underneath a bus with me and prevent an arms dealer from getting to a fair, I’m with them. I don’t have doubts about my decision to be an atheist. The doubts I have are more like yearnings. You wish there was something that was a supreme being that you could call on for justice and that could give you strength in those hours of need. Actually, we’re pretty much on our own. Mark Thomas is a comedian and activist. His latest book, Extreme Rambling: Walking the Wall is available from markthomasinfo.co.uk. He was talking to Jonathan Langley.

SPECIAL OFFER! – 3 months for just £6

Grab this Deal!

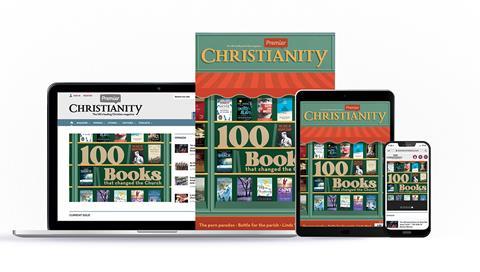

March’s issue of Premier Christianity opens with 100 books that have shaped the Church — how many have you read? Inside, we tackle the difficult reality of pornography within the Christian community, go behind the scenes with a Christian group touring alongside a world-renowned Pop star, and reflect on what it means to persevere in prayer. For a limited time, you can subscribe for three months for just £6.

*Offer applies in UK only, but check here for our overseas offers

More from Home

-

Archive content

Archive contentVicky Walker

2021-04-01T00:00:00Z

Vicky Walker is a writer and speaker, among other things. She writes about life, arts and culture, faith, and awkward moments in the form of books, articles, stories, and more, and she tweets a lot.

-

Archive content

Tom Holland

2021-04-01T00:00:00Z

Tom Holland is an award-winning historian, biographer and broadcaster. He is the author of a number of books, including most recently, Dominion: The making of the Western Mind (Little, Brown). He has written and presented a number of TV documentaries, for the BBC and Channel 4,on subjects ranging from ISIS ...

-

Archive content

Tola Mbakwe

2021-04-01T00:00:00Z

Tola Mbakwe is a multimedia journalist for Premier.

- Issues

- Topics A-Z

- Writers A-Z

- © 2026 Premier Christianity

Site powered by Webvision Cloud