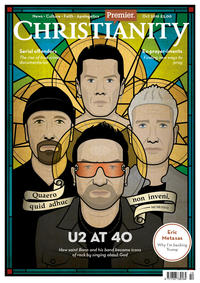

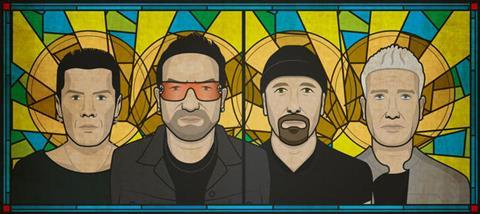

On Saturday, 25th September 1976, four teenagers decided to get together to make music. Forty years of faith-fuelled songs later, Steve Stockman charts the spiritual journey of Saint Bono and his band.

When the annals of 20th and 21st Century Church history are written, many heroes of the faith will make the pages. Billy Graham, Mother Teresa and Pope Francis will be among those heralded as saints who changed the global face of Christianity. But the historians would be remiss if they didn't also include the one rock band who, over the course of 40 years, have used the currency of their fame to literally change the world, and have done it from the foundation of a Christian faith.

As they reach this landmark anniversary, all the more poignant given their songs about both Psalm 40 and Isaiah 40, now is a good time to stop and reflect on the impact U2 have had on the Church and indeed the world.

September 1976 was no golden age in rock history. The top 40 was littered with bland and anaemic pop: Abba, Bay City Rollers, The Wurzels and (dare I say it) Cliff Richard. Something needed to change, and thankfully it did! The next year would see punk rock and the new wave transform the doldrums of 70s pop and prog rock. The Sex Pistols, The Jam, The Stranglers and The Ramones all brought vibrant new life.

During this gestation period, four teenagers from Mount Temple School in Dublin were getting together in the drummer’s kitchen. There was something blowing in the north Dublin air that they would later describe in the song ‘Lucifer’s Hands’: “The spirit’s moving through a seaside town / I’m born again to the latest sound / New wave airwaves swirling around my heart.”

Pilgrims on their way

As we celebrate 40 years of U2, it is hard not to plumb the depths of their most recent album, Songs of Innocence (Island Records, 2014), to gain some insight into what went on in Larry Mullen’s kitchen.

‘Lucifer’s Hands’ describes a collision of adolescent discovery that was about a whole lot more than just learning some chords, finding an echo box for a guitar and some words for the charismatic singer to croon.

There was something else blowing in the wind; another kind of charismatic in the swirl. The late 1970s was a time of Holy Spirit revival and renewal across the world. Dublin felt the refreshing impact of this as much as anywhere else. A number of house churches quickly appeared in the city. One was called Shalom and three of the boys rehearsing in that kitchen were soon a part of that fellowship.

The vortex of the swirling of adolescence, punk and Jesus created not only the world’s biggest rock band but gave them a dimension that no other rock band of this stature ever had: God. Another recent song, ‘The Miracle (of Joey Ramone)’ testifies to this blend and blur of faith and punk. Discovering Jesus and The Ramones around the same time shaped the music and honed a vocation. They were made “brand new” in spiritual rebirth. They were now “pilgrims on their way” in discipleship. It was a personal miracle that became a rock history phenomenon.

American author and minister, Frederick Buechner, has defined vocation as “where your deepest gladness meets the world’s deepest need”. U2 have done more than simply make chart-topping records. In the glare of stardom, they have been living out their Christian vocation.

Involved in the conversation

At the Greenbelt Festival in 1990, rock journalist, author and Christian thinker Steve Turner was giving a seminar about Christian engagement in society. He suggested that Christians have to be involved in the conversations taking place in our culture. He then used U2 as an illustration to suggest that they not only got involved in the conversation, but that they had actually changed its vocabulary.

Across four decades, U2 have made a significant Christian contribution to a vast array of conversations. When U2 sneak faith-filled words and ideas into songs, interviews or live concert settings, it never feels like a contrived mission strategy. It is simply a natural part of who they are.

I was there when they started conversing about the Troubles in Northern Ireland. It was at the Maysfield Leisure Centre in Belfast on 20th December 1982, when Bono explained how ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ was not a rebel song and that if the crowd didn’t like it he would never play it again. It was a song about the violence, but was also full of hope that the victory Jesus won could reconcile.

It wasn’t the last time they would break into the Northern Irish reconciliation conversation. Their biggest interruption was in 1998 before the Referendum on the Good Friday Agreement, when U2 played during a Vote Yes rally at Belfast’s Waterfront Hall. News footage was sent out across the world of Bono holding up the hands of the leaders on both sides of the conflict: Nationalist John Hume and Unionist David Trimble. The Yes vote won!

From the band’s War album until the end of the 80s, U2 conversed about US involvement in Central America, apartheid in South Africa and British miners, among other political situations.

The last line of 'Yahweh' must be one of the most suberversive moments in rock music

They were also putting theology into the mainstream. When they reached number one in the US charts on 8th August 1987 with ‘I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For’, radio stations across the world were ablaze with as succinct a theology of Christ’s cross as any hymn ever written: “You broke the bonds / And you loosed the chains / Carried the cross / Of my shame / You know I believe it.”

Remarkably, Christians missed the theological clout and actually wondered if the band members had lost their faith, distracted by the title. Philippians 3:12 is perhaps the biblical equivalent of what U2 were trying to say: “Not that I have already obtained all this, or have already arrived at my goal, but I press on to take hold of that for which Christ Jesus took hold of me.” It is worth noting that when contemporary Christian musician Amy Grant reached the top of the charts four years later with ‘Baby Baby’, her theology was not so robust.

A new dream

During the last week of 1989 at Dublin’s Point Depot, U2 said goodbye to the 80s and hello to the 90s with a series of concerts. Bono told crowds that the band had to go away and dream it up all over again. When Achtung Baby was finally dreamt up, it took U2 into a whole new conversation. If they spent the 80s singing about what they believed in, they spent the 90s singing about what they didn’t.

The message of 90s U2 can be understood by watching their two massive concert tours: Zooropa and PopMart. The former was a conversation about television and the modern phenomenon of media. The latter was an exposé of commerce and materialism. During the PopMart tour, Bono would stand like a tiny speck in front of a big screen, and during ‘Mofo’ sing “looking for the baby Jesus under the trash” as his hand gestured towards the kitsch of colour, giant lemons and the biggest outdoor film screen ever built. Jesus was still the centre of the thesis, but U2 were looking from another angle to find him in the mayhem of postmodernity. These were very powerful contributions to the conversation of changing times.

As the new millennium began, U2 shifted again. All That You Can’t Leave Behind saw them return to what they believed in. There was a maturity in the band’s work, attitude and spirituality. The content of that record was influenced by Bono’s activism, the Jubilee 2000 campaign and a book Bono had been reading: Philip Yancey’s What’s So Amazing About Grace? (Zondervan). ‘Grace’ was the last track and the central thought of that record: “Grace, a name for a girl / It’s also a thought that could change the world / Grace makes beauty / Out of ugly things.”

On the Elevation tour that followed, most nights would end with the song ‘Walk on’ and Bono getting the crowd to sing “hallelujah” while he declared, “The Spirit is in the house.”

During the Vertigo Tour in 2005, after the release of How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb, most concerts ended with a deeply spiritual trilogy: the personal testimony of ‘All because of you I am’ (the ‘I am’ referring to the name God gave himself when speaking to Moses); the commitment prayer that was Yahweh; and their old favourite closer from the 80s, a communal Psalm, ‘40’!

The last line of ‘Yahweh’ must be one of the most subversive moments in rock music. In a genre that tends to concentrate on sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll, here is the biggest rock band in the world closing out gigs singing, as an offering, with their hands held open to the Almighty: “Take this heart…and make it break.” That’s a conversation changer!

Encouraging others to converse

In 2008 I found myself at a songwriting retreat in Nashville. I was at the home of Charlie Peacock, who, after a few years on mainstream labels became a major guru in the Christian music industry. His influence on Christian artists had led many to cross back into the mainstream.

There were around 60 artists gathered in his Art House, a converted church that doubled as his home; a venue with a recording studio attached. What struck me very quickly was that almost every artist in the room was a Christian songwriter working in the mainstream. Had we been meeting ten years earlier, there was no way this would have been the case. As I started asking artists why they weren’t signed to Christian record labels, they all answered: “U2.”

U2 modelled another way for Christian artists to converse. From the late 60s with artists such as Larry Norman and Barry McGuire there had been a Christian underground that became its own industry. Christians would write Christian songs and use them to evangelise. The strategy usually centred around a church putting on a concert and inviting people in.

But being from Dublin, U2 had no such underground world or Christian circuit to play to. They had to take their songs out into the world rather than inviting the world in to hear them. By the beginning of the new millennium, U2’s success had inspired many other Christians to be salt and light. Jars Of Clay, Switchfoot, Sixpence None The Richer and OneRepublic are all examples.

U2 very rarely had any relationship with the Christian music industry. A surprise 25-minute set at 1981’s Greenbelt hardly counts! But in late 2002, Bono found himself at the heart of it as he embarked on a speaking tour of American evangelical churches to preach the need to respond to AIDS in Africa. It took him to Nashville, into that same room of Charlie Peacock’s that I would be in a few years later. When Bono visited it was full of the major Christian artists.

U2 have kept Christianity in the conversations of the age

After the meeting, Switchfoot’s Jon Foreman said: “I would not have dropped everything and booked a ticket at the last minute to hear a social worker discuss the problems in Africa…I am a selfish, star-struck, rich, American, Anglo-Saxon fan of Bono. He took a couple of hours to talk to a bunch of fans to tell them to use their clout to change the world…To feed the poor, to clothe the homeless, to heal the sick, to preach the good news of the kingdom of heaven. Sounds like an odd headline: ‘Bono Comes to Nashville to Convert the Christian Music Industry.’ I was convicted. Guilty.”

Changing the conversation

It would be an exaggeration to suggest that Bono changed the theology of social justice among evangelicals. However, it would be an oversight to leave him out of the story. John Stott said that the greatest evangelical heresy of the 20th century was ignoring social justice. Stott’s book, Issues Facing Christians Today (Zondervan) was published the very same week that Bob Geldof recorded the first Band Aid single. Bono was marrying his faith with Geldof’s development vision. This didn’t only find its way onto the songs on Joshua Tree, but Bono and his wife Ali headed out to Ethiopia to see it for themselves.

That experience would lie dormant for 15 years until Bono was approached by Christian Aid about Jubilee 2000. This Jubilee campaign changed Bono’s life and his justice work would in turn change the lives of millions across Africa.

In the 30 years since Band Aid and Issues Facing Christians Today, evangelical Christians have shifted from thinking of justice issues as an inferior social gospel to now regarding them to be an integral part of mission. I would contend that Bono contributed to that conversation.

If they'd listened to a prophetic word

Let’s break into this hagiography with a reality check. Bono is not everyone’s cup of tea. He has often been accused of having a Messiah complex, and the frontman would readily admit that he gets tired of himself!

He has never been one to make the Church feel secure in his membership, and he’s not short of a few expletives or shy to be caught with a bottle of Jack Daniels in his hand. He can at times be short of patience for religion. On the recent Innocence and Experience tour he celebrated Ireland legalising gay marriage. For those with a finely attuned Christian behavioural sensitivity meter, he can make you queasy.

Yet on the flip side, consider the following. Bono has sent video messages not once, not twice but three times to Bill Hybels’ Willow Creek congregation. U2 have invited Rick Warren to pray with them and the crew before a concert. Bono has sent Noel Gallagher Philip Yancey books after a discussion on faith. He was only too happy to show up to film a beautiful and informative documentary with Eugene Peterson about the Psalms. In the end, any close look at their career shows how U2 have kept Christianity in the conversations of the age at a time when faith is becoming more and more marginalised.

Early in their career, U2 were given a prophetic word that they should give up their music; that Christians shouldn’t be involved in such a world. At the time, Bono and the Edge considered leaving. Imagine if they had! Imagine U2’s contribution never appearing in the conversation of music and culture. Imagine the people reached by their campaigning left unaffected.

For 40 years U2 have made great albums, staged groundbreaking concert tours, fought AIDS, supported Fairtrade and pressed for peace in Northern Ireland. For 40 years they have done what they sang in the first song of their first album: ‘I Will Follow’. As they continue to follow, don’t be surprised if their best music is still to come and never be surprised at what they will do for the kingdom next. After all, 40 years on, they are still singing: “I believe in the Kingdom come / Then all the colours will bleed into one.”

Steve Stockman is a church minister in Belfast and the author of Walk On: The Spiritual Journey of U2 (Relevant Books)