There have been many analogies used to describe the idea that all religions are different ways to God. Many roads reach the top of the same mountain; blind men feel different parts of the same elephant, and so on. John Hick had his own favourite metaphor, borrowed from the Sufi poet Rumi: ‘One light, many lampshades.’

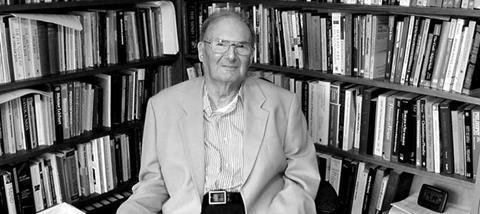

Hick, until his death in 2012 at the age of 90, was a leading philosopher of religion at the University of Birmingham, but it was in the mid-20th century that he made a name for himself developing a pluralist theology in which all paths lead to God.

It’s a view that has become increasingly popular within liberal religious circles. From Ghandi to Oprah, variations on the theme have penetrated the public consciousness. Jesus’ own claim to be ‘the way, the truth and the life’ (John 14:6), has become a jarring, even arrogant, statement to those who see it as a narrow-minded view of salvation.

SO MANY RELIGIONS

Having initially adopted an evangelical faith as a young convert, as an academic Hick began increasingly to question and reject core Christian doctrines such as the virgin birth and the deity of Christ. It led to a heresy proceeding against him at Princeton University in the 1960s where he was a theology professor for several years. The case was overturned soon after, but he became a rallying figure for other liberal theologians and churches of the day.

He described how his life experiences led him on a journey to question the view that Christ is the only way to salvation: ‘When I came to Birmingham University I became aware of people of other faiths. As chair of the city’s community relations committee, part of my job was to visit places of worship – so I was in mosques, synagogues, Sikh gurdwaras and Hindu temples.’

Hick came to the view that despite the external differences in terms of buildings, rituals and language, the core truths about God remained the same between religions.

‘It struck me that the same thing was going on in all of them as in the Christian churches – namely human beings coming together under the influence of some ancient tradition which enabled them to open their minds and spirits upwards.

‘I’ve also spent quite a lot of time in India with Hindus and Sikhs, in Sri Lanka with Theravada Buddhists and in Japan with Zen Buddhists. As a result of all this experience, it became fairly clear to me that there are many paths to God.’

BORN INTO A RELIGION

Even before experiencing multi-faith engagement, Hick had revised his early views on the centrality of Christ to salvation. The concept that Christ was the only way struck him as ‘a very strange thing to believe’, as his eyes were opened to the reality of the millions of people around the world born into thousands of other religions.

‘It is true of the majority of human beings that the religion which they adhere to depends on where they were born and by whom they were brought up. So anybody born to a Hindu family in India is extremely likely to become a Hindu, or in a Muslim context is extremely likely to become a Muslim and so on.’

Even the ‘inclusivist’ Christian view – that people of other faiths who genuinely search for God could be included in salvation through Christ – was not enough for Hick: ‘It would be very odd indeed if salvation is only available in one faith.’

REDEFINING GOD

Eventually, even the use of the term ‘God’ was contested by Hick. He preferred to use the all-encompassing phrase ‘Ultimate Reality’. His critics accused him of deconstructing the concept of God to something so general that it held little connection with people’s actual religious beliefs. For his part, Hick felt that he was drilling past the externals to the core of reality.

THERE IS JUST ONE LIGHT WHICH LIGHTS MANY LAMPS AND THOSE LAMPS ARE THE RELIGIONS

‘There is just one light which lights many lamps and those lamps are the religions. Many religious people of every faith affirm that there is an ultimate transcendent reality and our English word for this is “God”.

‘There are different concepts which have formed in the traditions that explore this Ultimate Reality. They have developed on the basis of religious experience but also all sorts of cultural factors. On the one hand we have this Ultimate

Reality in itself and on the other hand, different human awareness of it.’ Even the concept that ‘God is love’, something even the most liberal-leaning believer could normally affirm, became uncertain in Hick’s theology of a transcendence beyond human terms.

‘Ultimate Reality is not in itself a loving god, but it is expressed in many penultimate realities which are loving, such as the Christian faith. God in his fullness is beyond our understanding. It cannot be limited by any human definition – God is the ultimate mystery, in fact. This means that you cannot even say that God, in God’s ultimacy, is a loving person.’

ARROGANT AND INTOLERANT?

In many ways, Hick was ahead of his time. His views on the equal validity of every religion as a path to God, developed in the 1950s, are now embraced by millions of people. Those people may not possess Hick’s theological background,

but can easily grasp the central point: it doesn’t seem fair to exclude those who are born into a different religion, and to say anything else seems intolerant.

Yet religions are different, and often come to very different conclusions about the nature of God. Even Hick, in his own way, claimed a certain view to be the correct one – namely his own. At the centre of Christianity is an exclusive claim, that Jesus is the way to God, not simply one among many. The question is, does embracing that central belief leave Christianity looking inevitably arrogant and intolerant, as Hick claimed it did?