I’m from the charismatic/ Pentecostal zone of planet Church, where sung worship is loud, energetic, and frequently led by preadolescents who have poured themselves into impossibly skinny jeans. Despite feeling like Methuselah in some of these high-octane gatherings, it’s what I’m at home with. And so when the parish priest began the service with a parsonical drone that reminded me of a famous Mr Bean sketch, I bristled.

As the service continued, my mild irritation morphed into indignant anger. I have come to appreciate liturgy. Sometimes life renders us speechless, so to use the well-worn, life-tested words of others can be enormously helpful. But when the vicar’s voice transcended into full singsong mode, I seethed. Why couldn’t he use his normal voice?

When the time came for the sermon, I braced myself for what would surely be a brief homily of irrelevant twaddle. What happened next was shocking.

The sermon was brilliant. Concise, colourful and relevant – it was a work of verbal art.

But even more shocking was my response to this homiletical brilliance. I hated it. It irked me because my foregone conclusions were so wrong.

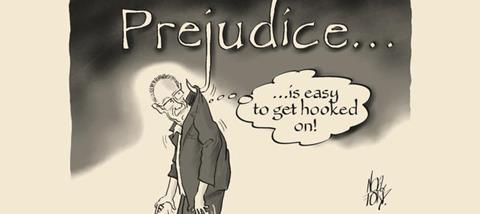

Prejudice looks for confirmation that we are correct, blinding us to any contradiction that might show our hypothesis about others to be wrong. When someone acts consistently with our blinkered view of them, we gladly nod, happy to be proved right, if only to ourselves. And when they do something that is contrary to what we’ve decided about them, either we don’t notice it – or if we do, we write it off as irrelevant, an out-ofcharacter, one-off aberration.

Prejudice can cause Christians to be very adept at labelling people. Someone steps up with a view (or even a question) that conflicts with our cherished convictions, and before even bothering to dialogue, we write them off by labelling them as being part of that group, (and they’re so wrong) which is inferior to our group, (because we’re unfailingly right). Meaningful conversation is silenced, and we hunker down in the trenches of our own opinions.

Jesus was a victim of this blinkered thinking. Despite the miracles that he performed, some of the religious barons of his day didn’t seem to notice them, and were only interested in criticising him because they saw him as a threat. And when the miracles were undeniable, because chronically ill people were made whole, or previously smelly dead folks like Lazarus were suddenly alive and hungry for lunch, the only recourse for Jesus’ critics was to insist that he was operating with dark powers.

The priest with the parsonical voice proved me wrong. Ashamed, I thought about apologising to him, and then decided that would be unhelpful. I’ve got a varied collection of bruises from Christians who have ‘confessed’ to me: they’ve hated me for years, they say – will I forgive them? Having unburdened themselves, they’ve walked away relieved, leaving me depressed at knowledge that I just didn’t need. And so, as we filed out of the church, receiving the customary vicarish handshake goodbye, I thanked the priest (perhaps a little too enthusiastically) for his wonderful sermon.

He smiled, and wished me a good day, using his normal voice.

But by then, thankfully, it didn’t matter which voice he used.