It’s not that my parents were consciously neglectful. But like swimmers hampered by leaden boots, frantically treading water just to stay afloat, they were preoccupied with survival and trying to hold a home together. My father had languished for five long years behind barbed wire, his youth stolen as a prisoner of war, until at last he’d escaped. His innocence stolen by half a decade of incarceration and near starvation, who knows what inner gremlins he wrestled?

My mother was abandoned by her father in infancy (one day he just walked out and never returned), and bruised by a bullying stepfather whose words and beatings kept her in a cowering posture right up until her death. So she too was a wounded soul, plagued by depression before depression really had a name.

And so I felt unnoticed. I know this, not as a result of much psychotherapy, but because I remember one very exciting day in our family’s life, one that embarrassingly shows how starved I was of attention. Our house was burgled. Not much was taken, but drawers were left flung open, stuff scattered everywhere as the robber searched in vain for something valuable to plunder. The police were called, and I, as the only one in the house when the crime took place, gave a statement. As it turned out, the thief did get away with something valuable that day, because the thief was me. I staged a break-in just to get noticed, and it worked.

Unmotivated, my scholastic achievements were lacklustre at best. Until I joined Mr Ruff’s class. An avid cricket fan and lover of real ale, Mr Ruff taught English, and quickly decided that it was a subject that I might do well in. This was very good news, because I was mediocre at everything else. History was dull, I hated my art teacher (the feeling was mutual) and I was so bad at maths that I didn’t even bother to show up for my exam.

But English…that was another story, literally. Mr Ruff told me that I was pretty good with stringing sentences together. More than that, he looked into a classroom filled with adolescents who were aghast at the idea that Shakespeare was interesting, and saw me.

One of my favourite Bible stories is the one about Zacchaeus. Jesus was passing through Jericho on his way to Jerusalem, fully aware of what would befall him there. But, despite this, he was not walking with his head down. Wonderfully, he saw the diminutive swindler, which was a big surprise, but one greater was to follow, as Jesus invited himself over for lunch. Probably prompted only by the joy of being noticed, at the banquet that followed, Zacchaeus announced his sudden retirement from swindling, and determined to make massive reparations.

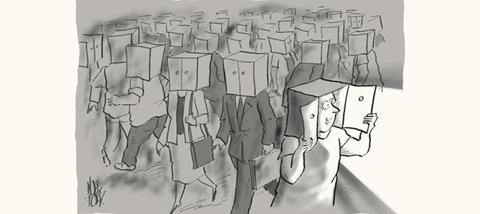

The Jewish theologian Martin Buber speaks of the distinction in our minds between treating people as subjects or objects. By objects, he meant our propensity for reducing people to being commodities to be managed rather than unique creations to be noticed. To the doctor, dear Mr Smith who has just recently been widowed becomes ‘the broken arm in cubicle seven’. To the salesperson in the shoe shop, the customer is an unwelcome interruption to her chatter about Saturday night plans.

Today, most of us will see people. So with God’s help, let’s take time to look, notice and, if appropriate, stop and really see people.