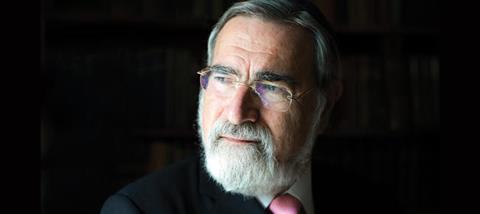

When Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks accepted the Templeton Prize this year he said something that stuck in my memory. He thanked ‘the God who believes in us so much more than we believe in him’.

His speech was peppered with other such memorable lines as he warned of the way the Western world has not only outsourced employment and skills, but also morality. Essentially, if you can pay for it, you have a right to it. ‘Ethics has been reduced to economics,’ he said, pinpointing in another pithy sentence the problem at the centre of our cultural crisis.

The Templeton Prize honours an individual who has made ‘an exceptional contribution to affirming life’s spiritual dimension’. Rabbi Sacks has made that contribution through writing, teaching and his role as a religious leader and public thinker, whose cultural analysis is deeply informed by the wisdom of his Jewish faith.

Judaism encourages questions. It doesn't silence them

Although he grew up in a devout family, Rabbi Sacks’ personal religious awakening occurred during his undergraduate years studying philosophy at the University of Cambridge. As a student he visited New York and was granted a rare interview with the esteemed Rabbi Menachem M Schneerson.

When the elder challenged the student over his Jewish peers at Cambridge who did not practise their faith, Sacks began to answer: ‘I find myself in a situation…’

The rabbi cut him off, saying: ‘Nobody finds themselves in a situation. You put yourself in a situation, and if you put yourself in that situation, you can put yourself in another situation.’

The challenge went deep for Sacks, leading to a rabbinical career that culminated in 22 years as chief rabbi in the UK. During that time he was credited with revitalising the Jewish community in Britain and has been a key figure in re-establishing the richness of Jewish thought, ethics and spiritual identity in the public sphere. In an increasingly secular age, Prince Charles’ personal tribute to Sacks as ‘a light unto this nation’ is a fitting one.

While his subject matter is serious, Sacks himself is less so in nature. Our conversation, which took place the day after he received the prize, included plenty of laughter. Perhaps the most memorable moment of the ceremony itself came towards the end when he was pulled up for an impromptu singalong with an assembled Jewish male choir, which he contributed to with gusto.

I believe in the same God that Rabbi Sacks believes in. We don’t, of course, share all the same beliefs. I believe that God has revealed himself in Jesus Christ whereas Rabbi Sacks does not. Yet as we spoke, we seemed to meet each other as close cousins rather than religious divorcees, acknowledging that the God who believes in us can also help us hear from each other.

When you received the Templeton award, you thanked the God who ‘believes in us so much more than we believe in him’. What did you mean by that?

I mean that he had the faith to create a universe out of which would emerge life and then us. If you read the opening chapters of the Bible, Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, and the generation of the flood, there’s the extraordinary line that ‘God regretted that he had ever created man and it grieved him to his very heart’ [see Genesis 6:6]. So it begins with divine disappointment.

After the flood, he [begins again] with Noah and kind of pledges himself, ‘maybe I’m going to be disappointed but I’m going to stay with it’. Therefore, it always seemed to me that our faith in him was pretty secondary in the scheme of things. His faith in us is absolutely essential.

That, of course, is really at the heart of Abrahamic monotheism. I always say that the Greeks gave us tragedy and the Hebrew Bible gave us hope. Judaism is the principle defeat of tragedy in the name of hope. That hope is grounded in the fact that our merely being here is testimony to God’s faith in us.

What were your first memories of your faith and the faith of your parents?

Until I was 3, we lived in a kind of extended family with my grandparents and assorted aunts, uncles and cousins in Finsbury Park, London. You began to get a sense that every Jewish family is a series of extraordinary stories. My grandparents on my mother’s side came from Lithuania but my great-grandfather had moved to Israel in 1871. He actually built the first house in one of the first towns in the new settlement of Israel. He was then forced to come to England in 1894.

There was something indefinably sad about the music of the synagogue, which I clearly remember from when I was around 2 years old. There was that sense of suffering and endurance that you could hear in the music.

In the synagogue, when we lift the Torah scroll and bind it, there are always some silver ornamentation bells that we place on the scrolls. As the grandson of Rabbi Frumkin, I was privileged to be given the job of putting the bells on the scroll when I was 2 years old! I think that began my endless fascination with the idea that in Judaism the holiest of holies isn’t a place or a person. It’s a scroll. It’s a book. And somehow, those words are God’s love letter to our ancestors and his laws of life. I think my fascination with the Torah, with the Mosaic books, began then and there.

At that special festival of Passover, during the Seder meal when we tell the story of the exodus from Egypt, the story has to begin with questions asked by the youngest child: ‘Mah nishtanah, ha-laylah ha-zeh?’ (‘Why is this night different?’). I think I can remember this huge extended family in my grandparents’ house and the first time I said, ‘Mah nishtanah.’

I learned a couple of things from that. Firstly, that Judaism is very child-orientated faith and that’s what makes us, paradoxically, one of the oldest of the world’s faiths but also one of the youngest because it’s so child-centred. I also learned the other really important thing about Judaism, which is that it encourages questions. It doesn’t silence them.

When you were chief rabbi (1991–2013), you sought to revitalise the Jewish Community in terms of its integration and what it offered British society. What did you think was lacking?

I wanted to explain that the fact that we had been Jewish in the past was no guarantee that our children would stay Jewish in the future.

Civilisations begin to fail when they lose the moral voice

If you can remember grandparents who spoke Yiddish and came from Eastern Europe, then you’ll stay Jewish, but our children are the children of the fourth generation, so we’re going to have to help them make it themselves. The thing we really did was to build a lot of Jewish schools, just because we couldn’t rely on tradition any more.

In a sense, you were evangelising your fellow Jews?

I think that’s doable because we don’t try to evangelise anyone else. That’s not because we don’t love everyone else, but we don’t think we have a monopoly on salvation.

Your bestselling book The Great Partnership was about the relationship between science and faith, responding to the new atheism. In an age of aggressive secularism, how are we supposed to steer the line today?

There was an American writer, Richard Weaver, who said that the trouble with humanity is that we forget to read the minutes of the last meeting.

There was a figure in the third pre-Christian century in Greece called Epicurus and there was a figure in late first-century and early second-century Rome called Lucretius, and these were both scientific materialists. Their work is very similar to the figures today. What fascinates me is when these figures emerged. Greece of the third century BCE was a civilisation on the verge of decline. The same is true of the Rome of Lucretius.

Civilisations begin to fail when they lose the moral voice and the moral inspiration that created them in the first place.

I can imagine if Dawkins was sitting here he would say something like, ‘What an incredibly arrogant thing to say. I’m a perfectly moral person and I don’t need God to be moral.’

Well, you probably need God to be polite, because he’s not very good at that! Atheists do tend to be very angry and very rude. Unfortunately, they also tend to think that they’re wiser than they are. I once heard an Oxford academic say about another academic: ‘On the surface he was profound, but deep down he’s superficial!’

You’ve had your run-ins once or twice with Dawkins…

I love him, let me be absolutely straight. He is one of the most brilliant science writers of our time, full stop. He goes around hitting religious people once in a while and we probably need to be hit! God sent Richard Dawkins for a reason. We are too complacent and we believe six impossible things before breakfast. We’re too credulous and we accept too much as the will of God, which we shouldn’t accept. So, just as Richard Dawkins sees religious people as part of the wonderful Darwinian plan of random genetic mutation, so I see random genetic mutations like Richard Dawkins as part of the divine plan. We each make spaces for the other in our universe. He’s a great man.

God sent Richard Dawkins for a reason

Muslims, Christians and even atheists often want to convert others to their way of thinking. But Judaism has never sought converts. Why is that?

Because if you read the Bible closely you see two things. In the book of Genesis there’s this whole problem of the Tower of Babel. If you read Exodus there’s the whole problem of Egypt and the pharaohs. And against that you set Abraham, who didn’t do any miracles, who wasn’t a ruler of any empire, or commander of any army. He just lived with his wife and tried to be a blessing to people around him.

I suddenly realised that Judaism is a protest against empires. An empire is something that seeks to impose a single truth, or a single system on the whole world. Judaism never believed that the Jewish way is the only way. The Bible is full of heroes and heroines who are much better than Jews and they’re not Jews. They’re just moral people.

Pharaoh’s daughter rescues Moses and saves his life and gives him his name. She was from the other side – an Egyptian and the child of a tyrant – but she was a good human being. The way that I see monotheism is not ‘one God, one truth, one way’. The miracle of monotheism is that unity in heaven creates diversity on earth. And that’s how I understand Judaism.

What’s your view of Jesus?

The first thing to say, and this is not the sort of thing people expect a chief rabbi to say, is that I grew up in Christian schools, surrounded by Christian friends and Christian teachers. I found that such a blessed experience. Here were people who took their faith seriously, so they understood why I took my faith seriously. The result is that I was given this extraordinary education in what it is to make space for people who are not like you and whose religion is not like yours.

I think you have to understand that Jesus is a figure who makes eminent sense in the Jewish context. He was, in one sense, an heir to the prophets. In another sense he was a rabbi of a very, very familiar kind.

We have great recollections of a rabbi called Hillel who went around teaching love and kindness towards strangers, who lived around a century before Jesus. A famous rabbi, Rabbi Akiva, who said that loving your neighbour is the fundamental principle of Judaism lived one generation later. So Jesus makes sense in that context.

The separation of the ways was really that Paul developed a concept that doesn’t really exist in Judaism: the concept of original sin. So, we’ve always believed that there’s actually nothing at all original about sin and we all suffer from it.

We have this great day, Yom Kippur, when we repent, confess, apologise, and we try and make good our wrongs. We don’t really need the death of Jesus to, as it were, neutralise the sin of Adam and Eve because we don’t see that sin as being transferred across the nations.

Another distinctive between Christianity and Judaism is that Christians believe Jesus was the Messiah prophesied in the Old Testament.

There were many messianic figures, all the way through history. When asked ‘Has the Messiah come?’ the mainstream voice in Judaism has always been the one that says, ‘Not yet.’ There’s a wonderful philosopher at Harvard called Robert Nozick, and in one of his books he writes: ‘When the messiah comes he will be met joyously by a group of Jews and Christians. They will come up to him and say, “Welcome messiah, we have been waiting for you for such a long time. It’s wonderful to see you. By the way, is this your first coming or your second?” And I’d advise him not to answer the question!’

Listen to this interview in full on The Profile podcast