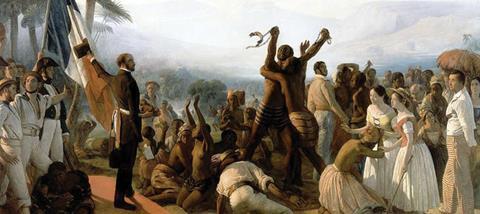

I come to the issue of slavery with a great deal of personal history. I am the descendant of slaves. My grandfather’s grandfather was born a slave in Antigua, in the last few years before the Abolition of Slavery Act came into force within the British Empire in August 1834.

Our American cousins had to wait a further generation for the 13th Amendment to the Constitution to abolish slavery in the United States in 1865.

The church in which I was nurtured to saving faith was formed as a direct response to slavery. In 1843 the Wesleyan Methodist Connection of America was formed as a breakaway movement from the Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) in large part because the MEC had not acted against some of its bishops in the American South who owned slaves. In response, the Wesleyans formed a church free from the tyranny of bishops and slavery and committed to holiness.

The problematic connections between churches and slavery are widespread. For example, United Society Partners in the Gospel (USPG) – the oldest Anglican mission agency – admitted in 2007 that it inherited slaves from the estate of Christopher Codrington in Barbados in 1710. USPG kept these slaves until the abolition of slavery in 1834, whereupon it was compensated along with a number of Anglican bishops at the time.

All of us have some personal history with transatlantic slavery because it was truly a global affair. The after-effects of such an industrial level of slavery remain with us. As Premier recently reported, Bristol Cathedral is considering removing its biggest window because of its links to Edward Colston – a slave trader. Several buildings, streets, and schools in Bristol are named after Colston because of his generous giving to his home town, but campaigners have said all links to him should be erased because of the way he made his money.

Another example of transatlantic slavery’s ongoing influence is how people described as West Indian are, paradoxically, mostly of African descent. Slavery also partly accounts for the great disparity of wealth, power and influence between former slave holding and former enslaved peoples.

This shared past and present means that we all too easily view slavery in the Bible through a 51 particular cultural and historical lens. In some respects, that lens can be a helpful one because we can relate the horrors of slavery to that of our own histories. In other respects, it can be deeply unhelpful because transatlantic slavery with its racially determined system can easily distort our perception of slavery in the Bible, which was quite different in many ways but nonetheless deeply oppressive.

SLAVERY IN ANCIENT TIMES

Slavery is in many ways the ugly underbelly of civilisation. In ancient times, it was a widespread practice. Only as civilisations and economies develop does infrastructure also develop which can both sustain and provide demand for slavery. Common routes into slavery in the ancient world included falling into debt, slavery as punishment, and the enslavement of conquered peoples. War made slaves and slaves were among the spoils to be gained by war. Some slaves were dedicated to deities and served in their temples.

In Sumeria, one of the earliest known civilisations, we find records dating back to 2100 BC which allude to slavery. Classical Greek philosophers Aristotle and Plato seemed to accept that certain forms of enslavement were part of the natural order. Throughout the empires of Alexander the Great, and of Rome which followed, slavery was part of the very fabric of society.

Slaves were legal property, rather than persons. Slaves’ bodies did not belong to them but to their masters, who could and did use and abuse them, both physically and sexually. Slave women who were lactating were in constant demand to serve as wet nurses for the children of their masters. Given the most common routes into slavery, women were more likely to be enslaved as conquered people than men, who were more likely to be killed, either in battle or to minimise future rebellion.

SLAVERY IN ISRAEL

The world in which ancient Israel was located was one in which slavery was unquestioned. Slavery was naturally part of the Israelites’ world view and the shared narrative of once being slaves in Egypt (Deuteronomy 15:15; 24:18) did not lead them to renounce slavery but rather to reshape it.

Israelites could buy slaves from the nations around them but were not to enslave one another (Leviticus 25:44-46). If Israelites sold themselves into slavery because of debt they were to be treated as hired workers rather than slaves and eventually released (25:39-40). Principally, this was because Israelites were to understand themselves primarily as belonging to the God who had redeemed them from Egypt (25:55).

It is doubtful whether Israel ever lived up to the high ideals espoused in Deuteronomy. Nonetheless, these ideals indicated that while Israel did not challenge the institution of slavery, Israelites were to have a different approach to slavery from that of the nations around them because they were themselves ultimately slaves of God.

SLAVERY IN THE NEW TESTAMENT

Slavery was even more deeply ingrained in the Greco-Roman culture of New Testament times. Jesus encountered slavery when he was asked by a centurion to heal his pais – most likely a slave (Matthew 8:6). In his parable in Luke 17:7 Jesus refers to one who has a doulon which is translated “servant” but perhaps should more appropriately be translated “slave”. Similarly, Jesus famously teaches that no slave can serve two masters (Luke 16:13).

Cornelius sent two slaves and a faithful soldier to summon Peter in Acts 10. When Peter was miraculously released from prison and goes to the house of Mary, the mother of John Mark, he is met at the door by a slave girl called Rhoda (12:13).

Christian slaves are instructed to obey their masters in Ephesians 6:5 and Colossians 3:22, and not to seek their freedom in 1 Corinthians 7. This is because in Paul’s view Christian slaves are free in Christ and Christian free persons are slaves of Christ.

Paul repeatedly describes himself as a “slave of Christ” (Romans 1:1; Galatians 1:10), though this is usually softened in translation to “servant of Christ”.

Slavery was ubiquitous in first century Greco-Roman culture. However, there were several common practices, such as idol worship, sexual immorality and eating food with blood which are condemned (Acts 15:20). Why was the enslavement of people not on the lists of prohibited behaviours? Are we to infer that the Church was more concerned about eating food with blood than it was about the enslavement of another human?

It’s true that there is no prohibition of slavery; however, the Bible is not silent on the issue. The New Testament speaks about slavery quite widely. It does so in two very important ways. First it adopts slavery as one of its primary metaphors. Second, it undermines slavery by redefining the true context of slavery.

MODERN SLAVERY

Across the world, modern slavery does not merely persist; it flourishes. Modern slavery takes many forms: human trafficking, child labour, sex workers, unpaid domestic servitude, bonded labourers, and those forced into marriage. Modern slavery is not something that happens elsewhere. Home Office figures estimate that the number of victims in the UK today could be as high as 13,000 people. Slavery is still very much a live issue. For more information and to join the fight against modern slavery, visit antislavery.org

SLAVERY AS METAPHOR

The practice of slavery was so deeply ingrained in the ancient world that the metaphor also became widely used. In Greek literature, we find the argument that one is always a slave to something or someone: to masters, to the law, to kings, to fear, to the gods; even the gods themselves were enslaved to necessity! The metaphor of slavery was an important and effective lens through which to reflect on the nature of freedom.

Paul uses this metaphor when he speaks of his own bondage to Christ by describing himself as doulos Christou, slave of Christ. In Romans 6 he uses this metaphor to great effect: “Do you not know that if you present yourselves to anyone as obedient slaves, you are slaves of the one whom you obey, either of sin, which leads to death, or of obedience, which leads to righteousness?…having been set free from sin, [you] have become slaves of righteousness (Romans 6:16,18, NRSV).

Paul uses a similar metaphor in the Philippian hymn where Jesus is described as taking on the form of a slave (Philippians 2:7).

In Mark, Jesus declares: “whoever wishes to be first among you must be slave of all” (10:44, NRSV). In the story of the washing of the disciples’ feet, Jesus not only takes the posture of a slave, he also concludes by teaching: “you also should do as I have done to you. Very truly, I tell you, [slaves] are not greater than their master” (John 13:16, NRSV).

The metaphor of slavery is widespread in the culture and the scriptures, at least in part because of its vivid imagery. To be a slave is to be wholly owned by another, to be fully submitted to another, to have no life of one’s own and to serve at the pleasure of one’s master.

In the same way that Christians took the cross, a symbol of shame and disgrace, and transformed it to become a symbol of hope and submission to God, so they took the metaphor of slavery and used it to describe their own devotion to God. Early Christians appropriated slavery as a metaphor for discipleship shaped by the cross.

UNDERMINING SLAVERY

Perhaps one of the most dangerous statements for the practice of slavery is to be found in Paul’s declaration in Galatians that “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (3:28, NRSV). This verse is in many ways a development of Leviticus 25:55, which reminded Israel that their primary identity was to be found in the fact that they all belonged to God. Paul’s words are a revolutionary declaration that the things which define and divide us cease to be definitive because the primary identity of Christians is rooted in Christ, where all human hierarchies cease.

Dignity is conferred on all persons because all have the potential of belonging to God. Indeed, the whole argument of Paul’s letter to Philemon is that his slave Onesimus is no longer just a slave but also a brother in Christ. That new identity supersedes his cultural social status. So although the Bible does not explicitly say “Thou shalt not enslave”, it certainly undermines the practice.

Moreover, general elements of Christian teaching are incompatible with slavery. For example, Jesus’ teaching to “love your neighbour as yourself” exemplified by the Good Samaritan in Luke 10, indicates that our neighbours include even those whom we might be inclined to despise. His teaching to “do to others as you would have them do to you” (Matthew 7:12, NRSV) if taken seriously prohibits the practice of slavery. Similarly, the view espoused in Genesis that all humanity bears the image of God also undermines the practice of slavery and all other forms of oppression.

Nonetheless, it is clear that these and other teachings did not constitute a direct challenge to slavery when they were written. Paul does not condemn Philemon for owning slaves or tell him that slave owning is incompatible with Christian identity. I suggest that this is because slavery was so deeply ingrained that Paul would have struggled to imagine a world in which it did not exist. Given that Paul appears to believe that the coming of Christ was imminent, his primary concern was not to right the societal ills of his day, but to prepare for Christ’s coming. This is why Paul has the audacity to say to slaves (1 Corinthians 7:21) that if they were slaves when they came to Christ they should not be concerned about it! Instead, he argues that Philemon must be a different kind of master because he is now himself a slave of Christ, and that slaves must be different kinds of slaves because they are now slaves of Christ.

ISRAELITES WERE ULTIMATELY SLAVES OF GOD

MAKING SENSE OF SLAVERY

The Bible requires that we work out the implications of its several arguments to determine what we believe and how we act. History suggests that we are very slow learners. Orthodox doctrines central to our faith such as the Trinity and the full humanity and deity of Jesus are similarly difficult to read off the pages of scripture. There is no single piece of scripture which encapsulates neatly the doctrine of the Trinity, no single proof text which unambiguously expresses the full humanity and divinity of Christ in the way that it is understood in our creeds. These are doctrines to which Christians are fully committed but it took the Church hundreds of years of careful reading and debate to work out the implications of multiple portions of scripture, which need to be read together in order to understand the person of Christ and the nature of God.

So it is with the issue of slavery. There is no single proof text to which we can turn to find an unambiguous condemnation of the practice. However, the internal logic of the scriptures to which we are committed and their overall trajectory, nonetheless, have led us to draw the conclusion that slavery is not only incompatible with Christian practice, it is incompatible with any understanding of what it means to have a shared humanity and a shared commitment to justice.

Reading scripture carefully, connecting its various arguments and following them to their logical conclusions will inevitably require that we engage robustly with issues of justice. Scripture will always point to the values of the coming kingdom. As Martin Luther King famously declared, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”