Discovering your children have special needs is like being given an orange.

You’re sitting with a group of friends in a restaurant. You’ve just finished a decent main course, and are about to consider the dessert menu when one of your friends gets up, taps their glass with a spoon, and announces that they have bought desserts for everyone as a gift. They disappear around the corner, and return a minute later with an armful of spherical objects about the size of tennis balls, beautifully wrapped, with a bow on each one.

As they begin distributing the mysterious desserts, everyone starts to open them in excitement, and one by one the group discovers that they have each been given a Chocolate Orange. Twenty segments of rich, smooth, lightly flavoured milk chocolate: a perfect conclusion to a fine meal, and a very sociable way of topping off an enjoyable evening. You begin to unwrap the object in front of you.

But you’ve been given an orange. Not a chocolate orange; an actual orange. Eleven erratically sized, pith-covered segments with surprisingly large pips in annoying places; requiring a degree in engineering in order to be peeled properly. You stare at it with a mixture of surprise, disappointment and confusion. The rest of the table hasn’t noticed. They’re too busy enjoying their chocolate.

You pause to reflect. There’s nothing wrong with oranges, you say to yourself. They are sharp, sweet, refreshing and zesty. Looked at from a number of perspectives – medical, dietary, environmental – you have been given a better dessert than everyone else. And you didn’t have a right to be given anything anyway.

But your heart sinks, all the same. An orange was not what you expected; as soon as you saw everyone else opening their chocolate, you simply assumed that is what you would get, too. Not only that, but this wasn’t what you wanted. And because you’re surrounded by other people, you have to come to terms with the sheer unfairness of being given your orange, while your friends share, laugh about and celebrate theirs. A nice meal has taken an unexpected turn, and you suddenly feel isolated, disappointed and frustrated.

Discovering that your kids have special needs is like that.

BEFORE PARENTHOOD

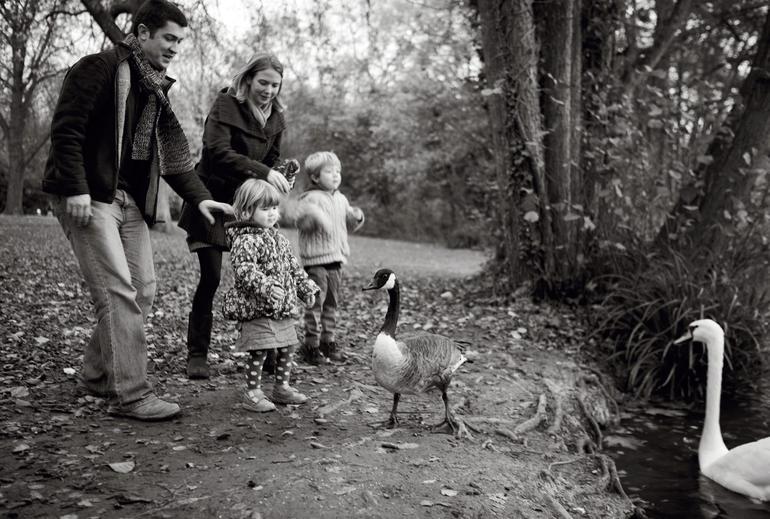

Before we become parents, we have all sorts of ideas and expectations about what it will be like. These ideas come from our own childhood, whether good or bad, from the media and from seeing the experiences of our friends and relatives: pushing prams with sleeping babies along the riverside, teaching our children to walk, training them how to draw with crayons rather than eat them, answering cute questions, making star charts, walking them to school. We don’t look forward to the more unpleasant aspects of parenting – interrupted nights, nappies, tantrums. Mostly, we daydream about the good bits, and talk to our friends about the joys and challenges of what we are about to take on.

Then something happens. For some of us, it is at a 12-week scan, or at birth; for others, it is several months or even years later. Something happens that tells us that all is not well. It rocks everything. The entire picture of our lives, both in the present and the future, gets repainted in the course of a few hours. Gradually, as time starts to heal, we come to terms with the situation, and learn that there are some wonderful things about what we’ve been given, as well as difficult and painful things. Yet we can’t help feeling isolated, disappointed, frustrated, even alone.

THE GIFT AND THE GUILT

Special needs, like the orange, are unexpected. We didn’t plan for them, and we didn’t anticipate them. Because our children are such a beautiful gift, we often feel guilty for even saying this, but we might as well admit that we didn’t want our children to have autism, any more than we wanted them to have Down’s, or cerebral palsy, or whatever else. We wanted pretty much what our friends had: children who crawled at 1, talked at 2, were potty trained at 3, asked questions at 4, and went off to mainstream school at 5.

Instead, we found ourselves in the life we never expected. At the age of 2, first our son, Zeke (now 6), and then our daughter, Anna (now 5), began regressing – that is, they started losing skills they had gained, and retreating into a teary bubble of fear and confusion. In the space of a few months, they lost the ability to sing songs, form shapes with their hands, or make eye contact with other adults. They lost speech (though not, thankfully, all of it), coordination and confidence. They started flapping and humming, standing on tiptoes, circling things, obsessing over objects, and bouncing up and down. Their diets, sleep patterns, social lives, educational needs and entire futures changed. They cried. We cried. They shouted. We tried not to. It felt like we were parenting upside down.

That all sounds very bleak. Often, it is. Yet the beautiful thing about having a heavenly Father is that even when everything goes dark, he is working, shaping, refining, teaching and growing us. Countless Christians for countless centuries – most of whom suffered far, far more than we do, given our world of anaesthetics and technology and relative peace and free healthcare – have testified to the things they have learned from God through pain and suffering. Many of us, for whatever reason, learn more in the valley than we do on the mountain. That has certainly been our story.

What not to say to a parent

Here are a few things people sometimes say that for many parents with disabled children, may not be that helpful, along with things which might work instead

LAMENTING AND THANKING

We’ve learned to lament, which is not something we’re generally very good at in the UK. In many cultures, when someone dies, those who have experienced loss are expected to process their pain loudly, corporately, articulately, publicly and perhaps musically: a noisy, guttural, wet, salty lament is widely acknowledged to be the best way to handle the emotion of the moment. In our culture, on the other hand, we weep in private as a family, reflect on happy times, put a good face on things, have measured discussions with funeral directors, tell our friends that we’re going to be ok, and then go about arranging a ‘celebration service’ (which must under no circumstances give the impression that anybody is sad about anything). We avoid lamenting, and end up simply venting, whether in person or online; meanwhile, our friends and family do their best to persuade us that it’s not really all that bad (which, in fact, it is). Learning to lament is vital, and biblical. Sadness, as Job and the psalmists show us, is better out than in.

Our children are both absolutely gorgeous and absolutely hilarious

We’ve learned to be thankful. Until a few years ago, thankfulness was simply a product of happiness; when we were pleased with how things were going (which we usually were), we thanked God for them, but it wasn’t a very intentional process. Now, we have become far more deliberate about thanking God for things that we could easily grumble about. (When Zeke wakes up at 4:15, we can grumble that it isn’t 5:15, or be thankful that it isn’t 3:15. In our case, those numbers aren’t hypothetical.) In doing so, we’ve noticed something powerful about grace. Namely: if what we think we have is greater than what we think we deserve, then that’s where thankfulness comes from – whereas, if what we think we deserve is greater than what we think we have, then that’s where bitterness comes from. Reflecting deliberately on how much we actually have, and how little we actually deserve, has made us thankful – for life, for children, for the gospel – all over again.

HOPING AND ADAPTING

We’ve learned to hope. Thinking about the return of Jesus to make all things new, generally speaking, is another thing we don’t do very well in our Christian culture, partly because (for many of us) the present is so comfortable. When you’re watching your children go backwards, on the other hand, you start to daydream about eternity; about the day when, in the words of JRR Tolkein, everything sad becomes untrue. You daydream about having ordinary conversations with your children, in a world free of autism, epilepsy and hyperactivity. In his beautiful description of the resurrection, Paul says that bodies which are currently perishable, dishonourable and weak will be raised imperishable, in glory and power (1 Corinthians 15:42-43).

That means that Zeke and Anna, in the new creation, will have brains that are able to reason and talk as if autism had never existed. They’ll be able to empathise, and understand social cues, and sit quietly thinking, and imagine what it’s like to be somebody else. We daydream about that. We imagine sitting round a dinner table with them, only instead of cajoling them into eating a cream cracker, we’ll be sharing wine with them, talking about why they like it, hearing them make jokes, and asking them about their travel plans. Having children with special needs has made us fix our eyes, more and more, on the unseen weight of glory that surpasses all hardship (2 Corinthians 4:17-18).

We’re learning to cope with mystery

We’re learning to adapt: we now think of it as normal to find a small boy squealing with delight on the trampoline, without clothes, at 6:30 in the morning, or for our daughter to pull the cushions off every chair in the room. We’re learning to pray (again), and the resources that have most helped us with that are shown in the box on p30. We’re learning to cope with mystery, particularly with the unanswered ‘Why?’ that haunts everyone who suffers. We’re learning to wait – for answers, for healing, for deliverance. Time and time again, God has shown us things that in all probability we would never have learned without difficulty. And in the midst of all that, our children are both absolutely gorgeous and absolutely hilarious.

Even so, there are times, when we’re wiping the citric acid out of our eyes and watching our friends enjoying their chocolate, when it feels spectacularly unfair. We wish we could retreat to a place where everyone had oranges, so we wouldn’t have to fight so hard against the temptation of comparison, and wallow in self-pity. We know that oranges are juicy in their own way. We know that they’re good for us, in a weird way, and that we will experience (and already have) many things that others will miss.

But we wish we had a chocolate one, all the same.

The Life You Never Expected: Thriving while parenting special needs children (IVP) is available now. Click here for more information.