Lucy Peppiatt explains how Black Christians living in slavery found inspiration in New Testament teaching

This month is Gospel Music Heritage Month, established in order to celebrate the rich history and cultural impact of gospel music in America and also now in the UK. This is a good month, therefore, also to celebrate African American readings of scripture, and a book I can’t recommend highly enough is Lisa Bowens’ African American Readings of Paul: Reception, resistance and transformation (Eerdmans).

Bowens’ book is a brilliant and eye-opening account of how African Americans read Paul’s letters in a way that actively subverted and overturned slave-owning and white supremacist distortions of scripture. These distorted readings had been used against them to maintain and institutionalise horrific practices.

Reclaiming scripture

Supposedly-Christian slaveholders regularly used Paul’s writings to perpetuate the myth of white superiority and enforce oppressive structures that kept the slaveholders in power and money and maintained the system of chattel slavery. It’s almost unthinkable for us today that the Bible was used in that way, but it’s a salutary reminder of what horrors people can commit in the name of God.

In her book, Bowens describes a greater power at work in the African Americans who found a message of freedom in the scriptures. That message – and it’s power – enabled them to challenge and dismantle the demonic use of the scriptures against them.

As Bowens writes: “The surprisingly provocative and powerful ways in which African Americans ‘rescue’ Paul from the clutches of white supremacy speak in profound ways to the power of black faith, the ability of black resilience, and the fortitude of black intelligentsia.”

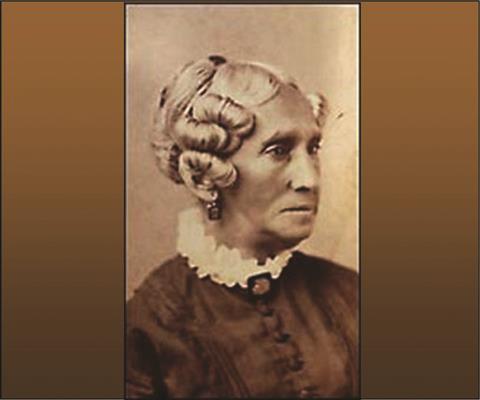

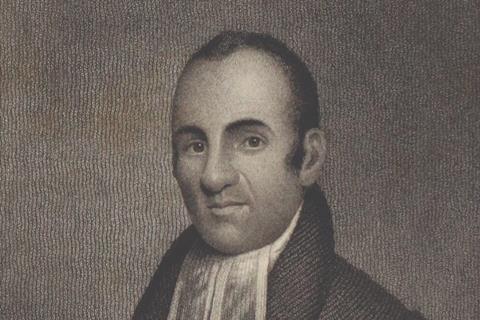

The book is a collection of a wide variety of literary genres: political speeches, essays, sermons, autobiographies and conversion stories, all of which demonstrate that the people who spoke and wrote these things saw themselves as “divine mouthpieces bridging the gap between the divine and human” along with Paul. It tells the story of people many of us will have never heard of: Jupiter Hammon, the first published African American Poet, Lemuel Haynes, the first ordained Black American, Zilpha Elaw, a renowned early Black woman preacher, Maria Stewart, the first female public lecturer on political themes and Daniel Payne, America’s first African American college president, among many others.

Paul becomes their friend and champion. Bowens argues that they “seized hermeneutical control” to protest against separation and dehumanisation and used Paul’s writings to support their view. As Bowens writes, they used Paul to give voice to their own “horrid stories”.

Theology that frees

How did this happen? Firstly, they knew that their bodies belonged to God and not the slaveholder. Secondly, they argued that they themselves were stolen property – in contravention of the command issued in Exodus 20:15 not to steal. Finally, they argued that the radical new birth of Christians formed a new humanity. Acts 17:26 was a key text: “From one man [God] made all the nations, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries.” They also protested that they could not follow Paul’s instructions for Christian households, as laid out in Ephesians 5 and 6, if husbands, wives and children were separated from one another. I found it particularly fascinating that early Black women preachers, Jarena Lee and Zilpha Elaw “anticipate a long trajectory in viewing Paul as an ally to female preachers”.

The very Bible that was used against him became the text he used to demonstrate God’s desire for his freedom

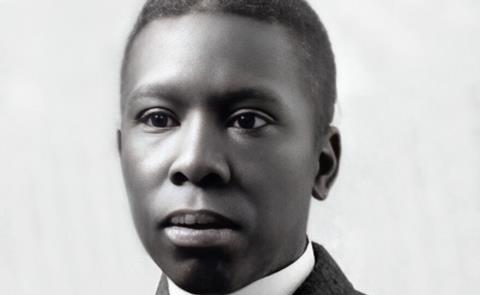

I loved all the stories, but one of my favourites was of John Jea and the miracle of literacy. Jea was stolen from Africa with his family, and cruelly and brutally treated when enslaved. Although he was illiterate, he realised “the slaveholder’s perverse tendency – utilizing Scriptures that sanction the despicable treatment of the enslaved and omitting Scriptures that would prohibit such behavior”.

At first, Jea hated those who professed to be Christians but, remarkably, having been forced to attend church by the slaveholder, he was radically converted, aged 15. Wonderfully, Jea then began to preach to his enslaver and the enslaver’s wife, declaring to them they could also be saved by grace.

Liberated and free

Quite clearly, Jea believed that the liberation of his soul should entail the liberation of his body and deliverance from the tyranny of the slaveholders’ hands and power. The very Bible that was used against him became the text that he used to demonstrate God’s will and desire for his freedom. Ironically, the slaveholder then banned him from attending church, but he continued to attend, on pain of more brutality and even death.

Eventually, he was freed and, amazingly, continued to pray for the slaveholder that he would find God. To do this, he asked God for the gift of being able to read the Bible in both Dutch and English so he might preach to the slaveholder. Bowens writes that: “after five or six weeks of prayer, God miraculously grants Jea’s petition by sending him an angel ‘with a large Bible in his hands’…The angel teaches Jea to read the first chapter of the Gospel of John, and when the angel disappears, Jea is not sure whether the event is real or not. Nevertheless, the Spirit speaks to him and assures him that he is able to read.”

Quite remarkably and miraculously, Jea was able to read the Bible from that day on. Although, equally remarkably, the Bible is the only text he was able to read. Bowens writes: “Jea’s ability to read the Bible, however, overcomes all these obstacles established by slavocracy, solidifies his freedom once and for all, and enables him to travel around preaching the good news to enslaved Africans and to all who would listen…Jea ‘literally reads his way out of slavery.’”

What is so apparent in these stories is the powerful work of the Spirit, giving enslaved Christians dreams, visions, wisdom, courage and the power to speak the truth. As the author puts it, we see the work of the Spirit “who allows them necessary agency to become critical interpreters of their contexts despite institutional constraints”. It is a deeply inspiring book from which we have so much learn.

No comments yet