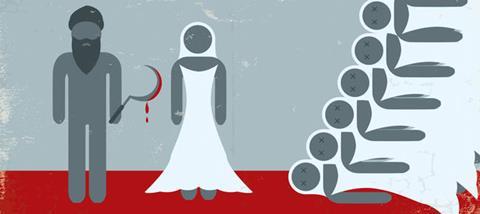

Islamists in Egypt recently tried to ban a new publication of the classic collection of stories Arabian Nights saying that it is ‘obscene’ and a ‘call to sin’. They have a point. Even in the opening story of the sultan and his new bride there are enough orgies and adulteries to convince him that all women are untrustworthy. After killing his unfaithful wife, he starts on his campaign of marrying a virgin every day then executing her after their wedding night. Scheherazade, the last of these brides, cleverly tells him a fascinating story on their wedding night, and her promise of a new one every night ensures her survival.

The Bible book of Esther tells a similar story of survival in the 5th century BC. Esther was at the last and most difficult stage in a yearlong beauty contest in Persia. If she lost, she’d be imprisoned within the king’s harem and forgotten about. If she won, she’d be queen. To do that, she had to spend the night with the king and ensure that he did two things: he had to remember her name in the morning, and he had to want to spend another night with her (Esther 2:14). The fact was: Esther had to be good in bed.

When Peter and Paul cite Aristotle’s three rules of submission, we should not automatically attribute these to God

Every year, little Jewish girls want to play the part of Esther when they act out this story during the feast of Purim. Of course, they are told that it was her beauty that won the king’s heart. But her beauty isn’t the only attribute they want to emulate. Esther was as plucky as she was pretty ? and her bravery saved the whole Jewish nation.

The king’s chief minister, Haman (I usually imagine him as a grand vizier with an improbable moustache), had plotted against the Jews and fooled the king into ordering their death. Esther saved her people by exposing the plot and convincing the king to foil it. It was a dangerous and brave thing to do, and needed great skill, because merely asking to see the king without being summoned risked the death penalty.

The place of women

In Esther’s day, Jewish lifestyle was under pressure from a new system of Gentile morality. The Persians and Greeks, who were fighting for supremacy, agreed on one thing: women were inferior to men. And while many feisty and independent women are celebrated in the Old Testament ? from leaders of the nation, such as Deborah and Miriam, to those who came from the bottom of society, such as Rahab and Ruth, ? women in Persian and Greek society weren’t even secondclass citizens; like slaves, they were barred from citizenship. Although poor women had to go out to work, the aspiration was to keep women at home as much as possible and in larger houses they were normally restricted to the women’s quarters.

By comparison, Jewish women had much more equality. Daughters had fewer inheritance rights, but even so, they fared better than younger brothers. The family’s land was inherited by the eldest son so that it wouldn’t get progressively split up. Whereas daughters hopefully gained some land through marriage, younger sons normally got just a small inheritance and had to seek their fortune elsewhere.

The role model for Jewish women was the outgoing and successful businesswoman in Proverbs 31. She succeeded in being a caring mother, a shrewd manager of her household servants, a craftswoman, merchant and profitable trader. She worked long hours so that her husband had time to be a political leader. She didn’t attempt to rule her husband, but she certainly wasn’t inferior to him. It was a very different family structure from the one that the Persians and Greeks were spreading throughout the world.

Three rules of submission

The new order for society was ‘every man should be the master in his own house’ (Esther 1:22, NASB). This was the decree of the Persian king after he had been drinking with his friends for seven days. He had ordered Vashti (the former queen) to come and ‘display her beauty’ (Esther 1:10-12).

Every man should be the master in his own house’ originated from a hungover king who was annoyed with his wife

When she refused, he sent this proclamation that a wife must obey her husband throughout his empire. This was part of the Gentile rule which Esther tried to defeat.

However, this new hierarchy in family life came to be the morality that won the day. Aristotle (in his Economics, about 400 BC) described a perfect household based on threefold submission: of a wife to her husband, of children to their father, and of slaves to their master. A couple of centuries later, the Romans adopted this model, saying that all three should submit to the pater familias ? the male head of the household.

By New Testament times, even Jewish authors were encouraging Jews to follow these three rules of submission, because otherwise they would appear as uncouth and immoral in the eyes of their Gentile overlords (Philo Hypothetica 7:2-3; Josephus CA 2:24-30). For similar reasons, Paul and Peter repeated the same three rules of submission to Christians ‘so that the word of God be not slandered’ (Titus 2:5; similarly Ephesians 5:22-6:9; Colossians 3:18-4:1; 1 Timothy 2:9-3:7; 6:1-2; 1 Peter 2:18-3:7).

Paradox

Not all words in scripture are spoken by God ? ‘every man should be the master in his own house’ originated from a hungover king who was annoyed with his wife. The Bible also quotes the fool who says ‘There is no God’ (Psalm 53:1) and Epimenides who says ‘Cretans are always liars’ (Titus 1:12). So when Peter and Paul cite Aristotle’s three rules of submission, we should not automatically attribute these to God and consider them to be part of his perfect law.

Jews and Christians followed Aristotle’s rules in order to avoid being dismissed as ‘immoral’. It is therefore an ironic paradox that many Christians still follow this lifestyle, even though gender inequality is now considered immoral by unbelievers.

Esther saved the Jewish people from Haman’s plot to wipe them out, but she failed to save their traditional family structure. As a result, Jews and Christians stopped celebrating women such as Abigail who overrode her belligerent husband’s decision (1 Samuel 25). And they even forgot God’s command to Abraham: ‘Obey whatever Sarah, your wife, tells you.’ But that, as Scheherazade might say, is a story for next time.