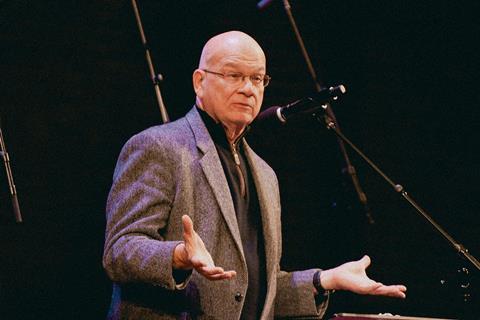

Timothy J Keller is the founding pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City and the author of award-winning title The Reason for God (Hodder & Stoughton). He talks to Sam Hailes about his latest book, Preaching.

Why did you decide to write Preaching?

The book is not a complete preaching manual. Instead it’s a manifesto of how to preach and communicate the gospel. It was my way of saying ‘here’s what I’ve learned in a place like New York City’ and ‘here’s how I think we can in a more sceptical age still preach the word’.

Are there common mistakes young preachers make?

There is no doubt that in theological schools and most preaching training, virtually all the emphasis is on…how do you outline a text, how do you understand these words and what are your reference tools? Almost all the training is there. Therefore the average younger preacher knows almost nothing about how to bring it home to people’s hearts. They don’t know how to connect. My book is to some degree trying to remedy that.

You defend expositional preaching and say it is usually best. Why is that?

In a relativistic culture, people need to see what the minister is saying is not just his opinion. He’s not just a pundit or someone writing on the opinion pages of a newspaper. Submitting to the text and saying ‘this is what this ancient text which has changed so many millions of lives says’ I think helps in a relativistic culture.

Many preachers say that receiving feedback on sermons immediately after preaching can be draining. But most would also agree it’s important to have that feedback. What do you think?

Feedback is crucial. It may be true that it’s emotionally difficult to get feedback immediately afterwards. You’re emotionally spent and to have someone come along and be clinical about it and say ‘that was good but not that part', is actually quite deflating.

However one of the things I did for many many years, and still do often is right after a sermon, right after the final hymn, I come down to the front of church and say anyone who wants to come and ask questions about the sermon or give me feedback, can do it.

I got anywhere from 50-150 people who always stayed. I would take questions. That was actually wonderful because I could tell almost immediately how people were hearing me.

You also need to have some mature Christian people who systematically give you feedback about everything, including whether you talk too fast. I really think that’s extremely important. You never stop needing it.

Mark Driscoll once told this magazine: ‘Name for me one young good Bible teacher that is known across Great Britain. You don’t have one. That’s the problem’. Was he right?

I remember that, by the way. I saw it somewhere. It wasn’t an unfair question exactly, but it seemed to me to lack insight.

What would have been a much nicer, kinder and probably more balanced thing to say would have been this: A generation or two ago you had a number of very visible Christian leaders and preachers. You had Lloyd Jones and Stott and other people perhaps not as quite well known. You had a lot of speakers and leaders who were high profile and formidable. It seems the last 30 or 40 years there haven’t been successors in the British Christian world. I’ve often asked why that is. And I’m not sure.

It might be that’s both good and bad. Rather than Mark looking at it almost ‘why don’t you have any celebrities like we do?’ There’s something about the British personality, unlike the American personality that’s deferential, it’s more self-effacing. You don’t promote yourself as much.

You’re a well-known preacher who has come to a level of public prominence a little later in life. For other well-known American preachers this level of public scrutiny comes much earlier in life, doesn’t it?

Yes, I started writing books when I was 58 years old. The books are what make you a well-known figure. I see my books going places and touching people that would never be touched if it weren’t for the book. So that’s great. But it also did bring that fame and profile and celebrity, frankly.

I actually tell younger ministers not to write. I’m so glad it didn’t happen to me when I was in my 20s or 30s. I think it would be very very difficult not to believe your own press. Media and publicity say ‘he’s the greatest at this’ or ‘the author is the leading this or that’. It’s the way you talk, and I get that, even though I cringe when I see it and it shows up on jacket covers all the time. If it started happening to me in my 20s I think I’d be more prone to believe it.

Some publisher comes and says, to every single young minister whose church gets big, ‘write a book because there’ll be a bunch of people who will buy it.’ These young guys start writing books which takes them away from preaching. You have to be very well leveraged to do that without neglecting your ministry in some way. Besides that, at that age they’re going to change their mind. 10 years from now they’re going to have different views on things so they’re going to be embarrassed by the books they write when they’re 32 years old.

I always say ‘don’t write! You’re not wise enough to write. You’re going to be so much smarter in 20 years’. I’ve begged people not to write books and by the way, most of the time they don’t listen to me.

Some have argued Jesus would have engaged far more in Q&A rather than long preaches. So why are so many sermons today 45 minutes to an hour long? Is this format grounded in the early church?

The educated guess by historical scholars is some of the sermons would have been more interactive and more like dialogues.

But some of them might have been a lot longer. It does talk about Paul preaching so long that Eutychus fell asleep.

In less industrialised times, people’s attention’s spans were much longer and preaching was much longer in the past. I just don’t think you can be too rigid.

Most evangelical preachers should probably shorten their sermons, considering changes in the culture. Even with solid Christians you need to be awfully interesting to keep people’s attention for 45 minutes.

Preaching (Hodder & Stoughton) is available now.

No comments yet