It is one of the oldest diseases known to man, and one that’s predominantly linked with poverty. But when Dan Izzett contracted leprosy he was living a comfortable life in the suburbs of Harare in Zimbabwe.

The retired pastor has battled constant pain since his diagnosis 40 years ago. His right leg has been amputated from below the knee and doctors are currently trying to save his left leg. He has, however, made a conscious decision to use his experience for good, and he and his wife now travel the world with the message that there is life after leprosy.

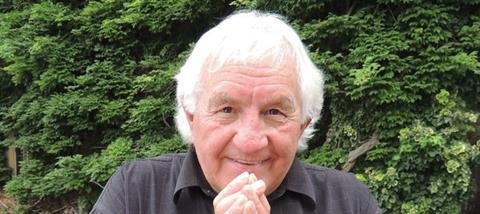

Izzett, 66, believes he has received a ‘God-given passport’ to reach out with hope to people affected by the disease. He has even chosen not to have corrective surgery on his ‘clawed’ leprosy-affected hands so he can connect with as many fellow sufferers as possible. He was talking to Christianity magazine while in the UK visiting his two children and grandchildren in Taunton.

Pain and peace

‘Leprosy is not hugely prevalent in Zimbabwe where I grew up,’ he says. ‘But now that I know something about the disease, I realise that I began to have symptoms at the age of 12 or 13.’

Izzett and his wife, Babs, now 64, had only been married for three months when he was first diagnosed in 1972. He was working as a civil engineering technician at the time and could afford to pay to be treated with a forerunner to multi-drug therapy ? the effective treatment for leprosy patients today. The pain caused by the disease was far from over though, and Izzett was admitted to hospital with what is known as ‘Type 2 leprosy reaction’ ? joint pain and lesions on the face and legs as thebody fights to rid itself of the dead bacteria during treatment.

‘I clearly remember feeling terrible in my hospital bed, when suddenly my room lit up with an awesome light,’ says Izzett. ‘I felt extremely peaceful and really relaxed, and a little while later my minister and Babs visited me and asked me what was different. I told them what had happened and my minister said, “I guess Jesus still visits those with leprosy.” I was happy to accept that something had happened. I still have pain today, but from that point in time there was a very good response to whatever drugs I have taken.’

A double blow

The couple were dealt a further blow in 1977 when Izzett’s wife was diagnosed as well.

Izzett, who became a Christian as a young boy, admits his faith has been tested over the years. ‘It would be unnatural not to ask, “Why me?”,’ he says. ‘But you just have to reflect for a moment, look at life and realise that at the end of the day our Father knows what’s happening to us. I have leprosy and my body has taken a lot of flack over it, but I don’t ever want to become a victim of the disease.’

In 1999, while working as a pastor at a Vineyard church, he and his wife had planted in Zimbabwe, Izzett felt prompted to do some advocacy work on behalf of The Leprosy Mission. He also felt it was right to tell his church congregation about his and his wife’s leprosy.

My body has taken a lot of flack, but I don’t ever want to become a victim of the disease

‘The church was full,’ he recalls. ‘We had told people we were going to give our testimony. We stood at the door of the church afterwards and every single person shook our hands and asked us over and over again, “Why did you not tell us before?”

‘It was very emotional.’

Leprosy colonies

Izzett has since travelled to India during his time as a board member for The Leprosy Mission International, and it was there that he saw what a blessing his clawed hands were.

‘Because I was a Caucasian visitor, there was no way people living in Indian leprosy colonies would think I was affected by the disease. But when doing the traditional Namaste greeting in India, where you put your hands together and bow your head, they were astonished to see that I had leprosy-affected hands. Suddenly no words were needed. They knew I understood and that we were all the same. It was my passport for connecting with them, human to human. It transcends language and race.

‘It was a deeply humbling experience, particularly when I was sat next to a man with the same amputation as me. But whereas I had a £4,000 state-of-the art prosthetic limb, he was using part of a plastic pipe to hobble around on.’

Fighting stigma

Izzett’s experience has spurred him on to battle prejudice. He and his wife have since spent many years travelling large parts of the world talking about their leprosy.

‘We’ve seen a lot and learnt a lot. Leprosy is easily treated; all leprosy drugs are now free. But the problem is locating the patients and getting the drugs to [them] ? that costs money. Many are in a bad condition when they come, so they need loads of medical care. It’s key to have early diagnosis and to have people on the ground. The fight against this disease is far from over,’ he says. ‘I’ve encountered stigma on the odd occasion and I’ve had to deal with that, but I want to eliminate that stigma and educate people.

‘For example, leprosy does not eat your flesh. What happens is that it numbs your sensation ? you have no feeling, you have anaesthetic feet, and it’s quite easy to burn yourself and to bump yourself. And that’s where the problems are.

‘It’s been extraordinary and so positive to be able to have God use us. We want to break open people’s hearts and minds to the message that leprosy is not what it is made out to be; that you can make a go of life.

‘Leprosy is not the end.’

Leprosy: The facts

Leprosy is a mildly infectious disease caused by a bacterium called Mycobacterium leprae (a relative of the tuberculosis bacterium or ‘TB’ germ). It can stay in the body for up to 20 years without showing symptoms.

Leprosy causes nerve damage which can lead to disability and the amputation of limbs. Leprosy also damages nerves in the face, causing problems with blinking, eventually leading to blindness. It is not hereditary and it cannot be caught by touch.

It is most common in places of poverty where overcrowding and poor nutrition and housing allow people to become moresusceptible to infection.

Leprosy is curable with multidrug therapy (MDT), which was developed in the 1980s. Within one day of starting MDT there is no risk of the disease spreading to anyone else. Lack of education, however, means that many people affected by leprosy are still stigmatised, even after they have been cured, especially if the disease has caused disability.

There are around 3 million people worldwide disabled as a result of late treatment of leprosy. In 2012, half of new cases were found in India.