‘He’s had a heart attack.’ ‘Has he got cancer?’ ‘He’s gone off with another woman.’ Parishioners of the village church in County Durham where I had been vicar since 1982 were trying to get their heads around the news that I had suddenly pulled out of all services and other ministry.

I was ‘off sick’ for the first time in my working life. It was 1987. The GP gave me the sick note, and I didn’t know what to do with it. The reason it gave for my absence was none of the reasons my parishioners had assumed, but depression. I was 37, and I would never be in paid employment again.

Now, in 2018, I am an OAP of almost 67. Thirty years on my life is still labelled with ‘depression’, along with the tags ‘general anxiety disorder’ and ‘social phobia’, among others.

Turning to poetry

During long hours alone, holed up inside my vicarage while the family was out, one of the ways I occupied my time was listening to the radio. The poet Laureate John Betjeman was being featured in a series. I found his poetic style not to my taste, yet the rhythms and cleverness were compelling. Around Christmas time I listened to broadcast evening services and carol services, missing the participation and leadership I would normally have had. I heard TS Eliot’s ‘Journey of the Magi’ read aloud in an extraordinarily rich and captivating way. It had me spell-bound.

One night I couldn’t sleep as a phrase kept buzzing round my head. I had to get up to write it down. It was the first phrase, it turned out, of a long, therapeutic scroll, whose lines came to me like tissues pulled out of a box.

Poet as well as priest

Over the following days I found myself writing again, sometimes shorter, more considered pieces, other time just blurtings: feelings to which I had to give vent. So began my calling to be a poet as well as a priest, and especially to give voice to sufferers, like me, from depression.

At that time, depression was deeply taboo in Christian, particularly evangelical, circles. To be depressed was regarded, often, as evidence of lack of faith, faulty discipleship – and seen as letting down the Lord himself. This attitude still persists today, but is extremely hurtful. I know deep within me that it is false too.

Depression and faith

Poetry began to give me a medium to explore not just the taboo, but the real relationship between depression and faith in Christ.

This poem was one of my early ones, now in the collection Hope in dark places. It’s called ‘Comfort’.

I dare, as a Christian, to be depressed:

to make the heretic’s admission of discontent,

of dis-ease and fear that will not relent,

I, who have drunk deeply of conversion’s cup.

I know I go on about it

but I refuse to be falsely happy,

to connive, to be clappy,

when all the time life is hell.

I don’t want to be cheered up,

prayed over, witnessed to, preached at, rebuked

like a deserter.

But I’ve looked

in the face of the triune God.

I’ve told him my grim tale

and, bless him, he kept his peace

and his eyes open. He sees

my grimness. That’s a comfort.

Hope in dark places

God loves me. It’s always been the case, no less now in what is a very serious illness. Several times I have been suicidal, many times in the reality of feeling no hope of recovery, no end to the horror of an illness that paralyses faith and worship, and is so very isolating. If you have no personal experience of clinical depression it is very hard to convey to you how awful it is.

To be depressed was regarded, often, as evidence of lack of faith, faulty discipleship – and seen as letting down the Lord himself.

So, my poetry collection, Hope in dark places, is something of my experience of how, alongside thorough medical treatment, God in Christ has been with me. He was there before me, in the wilderness, the Garden of Gethsemane, the cross of Calvary, the cold stone tomb and even in hell. And, because he has risen from the dead, victor over sin, death and depression (and every other affliction), there is hope. Real hope, not of a ‘magic cure’ but of his companionship on the road towards a recovery that grows here on earth but flowers in heaven.

It is aching hope, because I remain a depressive. In 2017 I had periods of dark depression that lasted for six months. But God remains, and will always be, faithful, loving, saving...

When I can’t hear you, O Lord,

Your Spirit finds a way to shout.

When I can’t pray, O Lord,

Your Spirit helps me to say what I need to say.

When I can’t say, O Lord,

Your Spirit helps me to feel what I need to feel.

When I can’t feel, O Lord,

Your Spirit feels for me.

When I’m at rock bottom, O Lord,

Your Spirit shows me you, here beside me,

there leading me forward.

When I’m well, O Lord, and find it easy to hear

and pray and say and feel,

I need your Spirit just as much.

David Grieve is a retired Anglican priest from County Durham as well as a poet. His collection of poems, Hope in dark places, is available now.

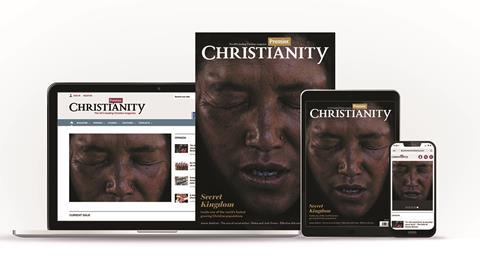

Click here for a free sample copy of Premier Christianity magazine