Day One, morning

THE CHILD BREADWINNERS OF BEKAA

In a side road in a small town in the Bekaa Valley, Yazan and Majed are hard at work. They are brothers aged ten and eleven. Their day started in darkness, getting up at 4am. They were a bit scared to be going out before dawn to get to their jobs in a local bakery. The tiny bakery turns out flatbreads for local restaurants. The boys work alongside two grown men. The adults receive $40 (£30) a day. The boys get $3 (£2.30) a day between them. But these meagre earnings are vital for their family’s survival after fleeing the war in Syria. Covered in flour and dust, the brothers clean the industrial mixing bowl, sweep the floors and pile the flatbreads neatly when they come off the hotplate. They do this sometimes until 10pm.

When the school bus goes past, carrying some of the refugees fortunate enough to be able to go to a local school, the boys stare out in sadness. “All we want is to go with them,” one of them tells me. “I want to go to school, so someday I can become a teacher.” His brother wants to be an engineer. When they remember their life in Syria, tears come to their eyes.

I have two sons, one just a little older than Majed, but their lives are a world away. It is heartbreaking to see that this is the reality for the children of the Syrian war. They’ve escaped the immediate danger of conflict, but their childhoods are slipping away in its wake. It’s children like these that CAFOD’s partner, Caritas Lebanon, are desperately trying to support. Having met Yazan and Majed, the charity is now figuring out how they can help the family and get the boys some schooling.

It can be done. Lebanon has opened some of its schools in the afternoon for a ‘second shift’ to accommodate the hundreds of Syrian refugee children in the area. The Lebanese children use the school buildings in the morning. The Syrian refugee children go in the afternoon, often packing out the classrooms to capacity. Caritas Lebanon is helping the refugee children access these places, supporting their families with the costs of clothing and equipment – and transport to get to school. It’s a massive logistical challenge. Many of the refugee families are in makeshift camps, or staying in poor-quality rented accommodation, and they can sometimes be hard to reach. But CAFOD and Caritas Lebanon know that, after the basics of life, the most vital thing the children of Syria need is to get an education. Whenever the terrible war ends, schooling – even at a basic level – will give them options. When the war in Syria began there were dire warnings of a lost generation of children. As the conflict grinds on into its eighth year – and the world is distracted by other disasters – the needs of that generation grow ever more desperate.

Day One, afternoon

“FUTURE? WHAT DO YOU MEAN BY FUTURE?”

It is Wednesday afternoon and we’re sitting on the floor of a shack covered in tarpaulin with eight-year-old Karim (pictured, above). This is where he’s been living with his family since fleeing Syria. He was up at 6am this morning picking potatoes in the neighbouring field to bring in a few dollars a week for his family. He tells me of the horrors they fled from just across the border. You can see the mountains they trekked across from the door of their hut. “A fighter jet came overhead and it hit our area. We had to flee at night and we never turned back. We had to rush quickly. Some people were killed and some managed to escape. We had to sleep in the open air – it was cold because we didn’t have enough clothes.”

Karim is just one of 150 children in the makeshift camp – one of many like it in the Bekaa Valley. Because there are no official settlements for refugees in Lebanon, this one is a jumble of breeze blocks and tarpaulins, muddy tracks and old farm machinery. It’s a desperate place to try to raise a family, and winter is coming. The hardship in the coming months will be unimaginable. CAFOD and Caritas Lebanon’s immediate work here is to make sure the families have enough warm clothes and blankets.

The saddest part of our chat with Karim was when we talked about school. He is totally resigned to not going – as if even the thought of it now is baffling. “Every child should get a chance to go to school – but here there’s no opportunity. I work to help my family and that’s it.” I ask him what he dreams of in the future. He almost laughs. “Future? What do you mean by future? It’s difficult to answer. Life is difficult. I don’t have a dream.”

Day Two, morning

“I WANT TO BE AN ENGINEER SO THAT I CAN REBUILD SYRIA”

Thursday morning and we’re up before dawn to take the winding road to Mount Lebanon. It’s a beautiful clear day as the sun comes up and we arrive at the home of a family of six refugees from Syria. They’re living in a couple of rooms in a house that is still being built – but there’s a stove burning and the four children are happily pouring tea and having breakfast. And, even better, Hussein, 11, Mostafa, 10, and Amar, 6, are just about to put on their school uniforms.

This is the bit of the day my kids sometimes moan about as they jam on their shoes and shrug on their blazers. But these three children can’t get their new school shirts and smock on quickly enough. Just a few weeks ago the boys would have been heading out at 6am to go to work: Hussein on a building site, shifting wood and helping with cement, and Mostafa in a local shop, cleaning the floors and helping the customers. But Caritas Lebanon has helped them get a place at a school nearby that is stretching itself to its limits to help Syrian children. It means that for the first time they’ll start to learn to read and write. Caritas Lebanon pays for the transport to get them there, the clothes they need and the pens and pencils to do their work.

The children are so proud to be putting on their uniforms – Hussein spends a few moments combing his hair and passes the comb to his little brother who copies him. Their sister ties her hair in a ponytail and does up her winter boots, beaming. If you needed any proof of what confidence and joy the simple act of getting ready for a day of learning gives a child – this is it. Our cameraman, Ben, gets on board the school bus with them. It’s rammed with children – the vast majority Syrian refugees – an indication of the pressure Lebanese schools are under.

These lucky children are off to a school nearby. It used to cater for just 60 Lebanese children – now it has more than 200 Syrian children alongside them. The Sisters could easily look worn down by what they’ve taken on – but they don’t. They’re so joyful as they greet the children off the bus and line them up before class.

Our little family stand proudly in line, the brothers one behind the other. They remind me of the two brothers we filmed in Bekaa who have to work in the bakery. They would give anything to be here like Hussein and Mostafa. Later, in a break from class, we sit and have a chat with them. Their new lives, however temporary, are going some way to healing the pain of what they left behind in Syria. They speak vividly of the bombing of their home and their struggle to escape – walking over the mountains, sleeping in the open air and being terrified of wild dogs. But even just a few weeks of education has given them new hope. It’s allowing them just to be children. And, most importantly, it’s letting them think of the future and make plans. And what’s touching is that their real home and Syria are never far from their minds. I ask them what they want to be when they grow up. “I want to be a doctor,” Mostafa tells me, “so that if people get injured and are hurt, I can help make them better.” He turns to his brother who tells us straightaway: “I want to be an engineer so that I can rebuild Syria to make it just like it was before. Now that I can read and write, we can gather everyone together again to rebuild all those destroyed homes.” It’s a shared dream of mending broken people and resurrecting a shattered country.

And with that, they run back to their classrooms.

Day Three

BRINGING CHILDHOODS BACK TO LIFE

I’m flying home early in the morning today. As we wind slowly upwards away from Beirut, I’m thinking of all the children we met and what they might be doing. It’s hard to fully comprehend what a huge influx of refugees can be like for a small country. In the last seven years, Lebanon’s population has grown by a quarter – 4 million Lebanese living with 1.5 million Syrian refugees. Syrians are in almost every community – and we’ve seen it this week. There are families living high in Mount Lebanon, tucked into spare rooms in villages. There are makeshift camps in the Bekaa Valley, tiny homes made of wood and breeze blocks, which will freeze in the winter. There are families living in cramped and poor accommodation in the heart of Beirut – a city that feels as though it’s bursting at the seams.

Be in no doubt what Lebanon has taken on, while countries in Europe have bartered and grappled with how many refugees they are prepared to let in. It is extraordinary. Lebanon has tried hard: packing out the classrooms as much as possible and working to ensure that Lebanese children know to welcome their neighbours. It is sometimes very difficult.

And as the war wears on across the border, the task facing this country and the aid agencies is getting harder and harder. Funding for refugee support is falling. The world has other crises to respond to: the Rohingya, Indonesia, Yemen. But to leave the children of the refugee families without adequate support and – crucially – some education, will spell disaster. However, the bottom line is that it’s simply impossible for every Syrian refugee child to go to school. 250,000 are getting no education at all. Many families need their children to work in order to buy food. Some families can’t dress their children properly to go to school, can’t access any transport or pay for basics like paper and pencils.

That’s why CAFOD’s work here is so crucial. The money raised back in the UK is making a huge difference to children’s lives. Some of it still has to go on the basics of life: warm clothing as winter approaches, sanitary help, health support and clean water. Not to mention psychological support for those traumatised by the conflict. But for the children, saving a life entails much, much more. At the moment, those in the worst conditions and without schooling are seeing their childhood literally ebb away day by day. It’s the slow degradation of a young human life. To lose the capacity for hope, for aspiration, for the dignity that an education provides, is to lose life – not in a physical sense – but in all its fullness.

We saw what a difference even a little education makes. The pride in buttoning up a school shirt, combing your hair, getting out of the house on time to catch the school bus, full of happy chatter.

It’s unimaginable what these Syrian children have witnessed and endured in their tenderest years. It’s impossible to tell how soon they’ll get the chance to go home, and what they might face when they get there. But little by little, the work of CAFOD and Caritas Lebanon is bringing their childhoods back to life.

Julie Etchingham presents ITV’s News at Ten, and fronts their major current affairs shows Tonight, Exposure and On Assignment. She also led ITV’s coverage of the wedding of the Duke and Duchess of Sussex, and in 2015 became the first woman to moderate a general election leaders’ debate

The names of the children mentioned in this article have been changed. To donate to CAFOD’s Syria Crisis appeal or to find out more visit cafod.org.uk

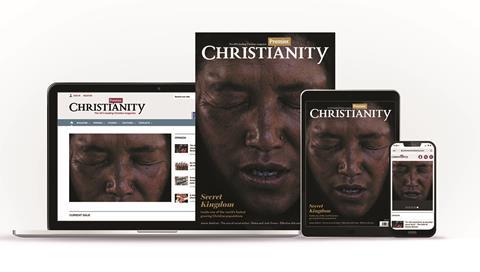

Get more articles covering news, culture, faith and apologetics in every print issue of Premier Christianity magazine. Subscribe now for HALF PRICE (limited offer)