Martin Saunders sees if there’s anything we can learn from Channel Four’s new show.

Rumours of my demise have been greatly exaggerated. Please forgive me, dear reader, for leaving you in more capable hands for not one but two months; in my defence, my regular diet of cultural feasting had been somewhat interrupted by the copious bottom wiping of a new arrival in the Saunders household. It’s tricky being a culture columnist when you’re only allowed to watch the TV on mute, and the only music you can discern is a haunting midnight wail that rings on long after the baby is asleep. Life, and young Samuel Saunders, have since settled down however, and thus I return, although unfortunately so do the three pictures of my head that make me look like I’m following a smell.

Politics has been funny for a while. BBC2’s topical news quiz Have I Got News For You has endured for more than two decades, building its success on the flaws and failings of the British political system. Like panellist Ian Hislop’s oft-sued satirical magazine Private Eye, the show pulls no punches in critiquing Westminster, and while it often goes for big laughs above serious analysis, it does provide a kind of extreme political scrutiny.

HIGNFY doesn’t exist for this purpose however; it is a piece of light entertainment programming designed to appeal to those of us who take an interest in news and politics. It is a partner show to Newsnight or Question Time; the light relief to complement more hard-hitting journalism. Both strands have long histories – in the 1970s and 80s you could even flip channels between the nine o’clock news and Not the Nine-O’Clock News; before that The Frost Report gave satirical balance to the earnest political programming of the 1960s.

In January, Channel 4 launched a new show which sought, perhaps for the first time, to draw these two programming strands together. Commissioned for an initial run of 15 Thursday nights, 10 O’Clock Live is an attempt to create television that is both hard-hitting and funny; both analytical and satirical. Fronted by comedians David Mitchell and Jimmy Carr, satirist Charlie Brooker and presenter Lauren Laverne, it mixes interviews, sketches and monologues, all of which aim to simultaneously hit comic and political notes. So in the first show, Mitchell chaired a serious debate about bankers’ pay, but was unafraid to ridicule his guests in a manner of which even Jeremy Paxman would stop short. Carr fronted a sketch about rioting in Tunisia which was played totally for laughs, but then Brooker provided a mainly serious opinion piece about potential future Presidential candidate Sarah Palin. That’s not to say 10 O’Clock Live doesn’t know what sort of show it is – for me that’s lazy critique. Rather, it is attempting a very bold balancing act which has the potential to tread new ground, in the UK at least.

The American Precedent

10 O’Clock Live has clearly drawn inspiration from two US TV shows which have managed, with impressive regularity, to achieve the mix of serious political discourse and seriously funny gags. The Daily Show with Jon Stewart is a 30-minute late-night comedy programme broadcast across America on Monday to Thursday evenings. The show reports political news, but points out areas of hypocrisy, policy flaw, imbalance and idiosyncrasy. Recording in front of a live studio audience (10 O’Clock Live does the same) gives the programme a fresh dynamic, with Stewart able to play off the crowd. In the light of the country’s opinionated, personality-driven right-wing news media, the show is a breath of fresh air, and has gained a strong following at home and abroad.

The success of the format, and the fertile comedy territory of Republican-friendly media that it exposed, led to the birth in 2005 of a spin-off show, The Colbert Report, which now airs directly after The Daily Show. The show is much more a direct parody of Rupert-Murdoch’s right-wing TV channel Fox News, and in particular programmes such as The O’Reilly Factor.

The influence of both programmes can be seen in 10 O’Clock Live, yet the British show also has its own unique flavour, most clearly seen in the way that all four presenters are given equal billing, with no clear host. It is less slick, as might be expected, and at an over an hour, has to sustain the balancing act for much longer. Early reviews were mixed, but the show’s target audience of thinking 20 and 30-somethings is legendarily hard to please. With three months to find its feet, and with a wealth of talent involved, the show has every chance of being regarded as the ‘British Daily Show.’

March for something

New formats happen for a reason. Channel 4’s executives have perceived a cultural shift that makes a show like 10 O’Clock Live legitimate and timely. So what exactly is that shift, and why does this show work now?

First of all, comedians tend (although not exclusively) to lean toward the left, and as The Daily Show has found, it’s much easier to be funny when you’re in opposition. It is somewhat lazy to characterise right-leaning politicians as the bad guys, but in a time of economic downturn, doing so does carry a degree of resonance. Second, and again thanks in part to the recent recession and the MP’s expenses scandal that accompanied it, trust in the political process are at an all-time low. Politicians are caricatured either as aloof old Etonians looking to feather their own nests, or as compromising turncoats who’ll sacrifice election promises in the pursuit of a little more power. The notion of British democracy feels a little hollow; the recent marches against university tuition fees seem to have had exactly the same effect as the estimated million-strong protests against the war in Iraq, raising the question: are we actually electing five-year fixed-term dictatorships?

As a result, there is a sizeable element of the public that no longer wants to take politics entirely seriously. They want to laugh; they want to see their cynicism validated. 10 O’Clock Live serves them perfectly, but more optimistically the show potentially has another, less jaded audience. Comedy, and the popular faces who present the programme, could act as an entry point into politics for younger viewers, and it doesn’t necessarily follow that the process will infuse them with cynicism; rather it could provoke them to response.

In the US last year, Stewart and Colbert hosted a joint rally in Washington to promote ‘reasoned political discussion’ The socalled ‘Rally to Restore Sanity’ drew over 200,000 people. So while the activists have become cynical and tired; they’re still activists. Could 10 O’Clock Live provoke the same kind of engagement in the UK?

Aiming at the hard-to-please

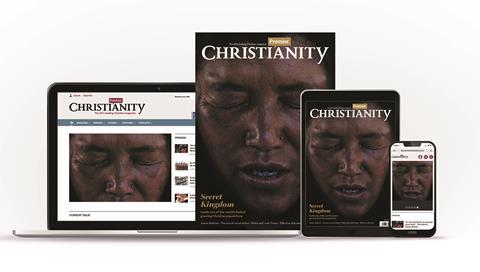

A glance at the cover of this magazine will reveal that, like Channel 4, the Church is facing up to the issue of connecting with a generation who have rejected traditional ‘programming’. Just as 10 O’Clock Live seeks to re-engage the 20s and 30s through innovative means, Christians now have to listen to this massive, largely absent age group, and try to understand what it will take to bring the church back to them.

We – at 32 I write from experience – are a cynical generation, suspicious of earnest men and women and their institutions. We use and respond to humour because it cuts across rhetoric and otherwise-unchallenged nonsense. Yet we still believe change is possible; like the 200,000 who marched in Washington, we want to be activists, as long as we feel the world is being honest with us. Those statements apply just as much to political engagement as they do to matters of faith.

The idea that change is possible is, I believe, what drives people like Charlie Brooker and David Mitchell to make a show like 10 O’Clock Live. If you cut through the layers of satire and ridicule, you find people who genuinely believe that while politics has lost its way, it is worth fighting for.

So it should be with us. Could 10 O’Clock Live, and the journey that has birthed it, be a useful model for the Church as it seeks to re-engage its missing generation? Perhaps. If we’re prepared to listen to them, and even to reshape church as we know it to accommodate them, we might even see a new wave of 20s and 30s Christians who are not just consumers of a product they feel is for them, but a movement of activists, rallying back to God.

Martin Saunders is an author, screenwriter and the editor of our sister title Youthwork magazine.