I cannot help but sympathise with Noel Conway. He has the most common form of Motor Neurone Disease (ALS) and has argued in court that doctors should be allowed to prescribe him a lethal dose of drugs when he feels his life has become unbearable.

Last week he went to the Court of Appeal to argue the 1961 Suicide Act is a "broken law". Under the current legislation, anyone who assists Mr Conway to die would be liable to up to 14 years in prison.

I too have a form of MND; mine is PLS, a very prolonged form of the disorder. I can utterly understand his fear of increasing dependency, becoming ‘entombed’ in his body and dying. However I’ve long argued that legalising assisted dying is fraught with dangers and not the way society should go, no matter its attractions. Its implementation elsewhere in the world raises more questions than answers.

I was diagnosed in 2002 and since then I have become increasingly disabled and dependent on others for the daily tasks of living. I now completely rely on Jane, my wife, who assists me with all aspects of daily living. She is my life-support system. I expect my continued gradual decline eventually to kill me. Yet life is very good.

Of course I have sympathy with Noel Conway. I’ve lost several friends from MND, and know it’s a hard road. However his backers, Dignity in Dying (the old Voluntary Euthanasia Society), foster a misleading impression about the final stages of MND, that it is frightening and painful. Mr Conway says unless he goes to Switzerland at great expense, he will “effectively suffocate”. However the MND Association’s End of Life Guide gives a more informed account: “In reality, most people with MND do not die from a frightening event, but have a peaceful death.

“The final stages of MND will usually involve gradual weakening of the breathing muscles and increasing sleepiness. This is usually the cause of death, either because of an infection or because the muscles stop working.

“Specialist palliative care services focus on quality of life and symptom control. This includes practical help, medication to ease your symptoms and support for you and your family…For people using ventilation, the palliative care team will be able to offer advice about when it might be best to discontinue its use.”

In truth, Noel Conway’s case is less about him than about changing the law (as he wants). Parliament has repeatedly resisted this. There are good reasons for not doing so.

- All human life is precious, however damaged, however weak, young or old. It deserves absolute protection. The law as it stands does that: all proposed changes fail to. Once you open the door and legalise the intentional ending of life, you cannot close it again.

- Experience in foreign jurisdictions has proved that a limited initial law always gets extended. A suicide pod enabling occupants to kill themselves at the press of a button recently went on display at an Amsterdam funeral show.

- As it stands, the law protects disabled, depressed, or chronically ill people and the elderly with dementia – in fact, all who are or feel themselves to be a ‘burden’ on their family or society. Once you allow euthanasia in whatever form you put them in danger, either from external pressure or just from feeling, “I should”. Abuse of elderly, disabled and hospitalised people is all too real. Removing the taboo of ending life would further jeopardise the most vulnerable among them.

- The argument that, ‘It’s my life; I should be free to choose,’ ignores the fact that we live in societies. Our actions affect others. We’re not free to drive on the wrong side of the road; it would endanger others. Changing the law would put many at risk.

- Assisting suicide is mistaken as compassionate – compassion does not mean killing someone. It means accompanying them on the road of their suffering to the end.

- Palliative care was pioneered in this country and is second to none. It still needs more research and wider provision. To introduce assisted dying would remove the impetus from such improvement by providing a cheap alternative, for it’s true that the cost of good palliative care dwarfs a lethal dose of barbiturates. We are in danger of elevating cash above life. The attraction to politicians of saving money is obvious. But I don’t want to live in a country where money matters more than life, nor where my carers might be my killers.

Near the end of her great book of women’s experience of World War 2, Svetlana Alexievich records these words of a medical assistant who survived the whole war on the front line. She recalls rescuing two badly wounded men from the battle of Stalingrad, only to discover that one was German and facing the dilemma of whether to leave him to bleed to death: “I went on carrying both of them.” She says, “… human life is such a gift…A great gift! Man himself is not the owner of that gift.”

In the crucible of the most acute of suffering Tamara Umnyagina had discovered the great truth, that we don’t own our lives. For Christians, everyone’s life is inalienably precious. That’s the reason for the command, 'You shall not murder' (Exodus 20:13).

Contrary to what some advocates of assisted suicide claim, the Hebrew here includes causing death through carelessness or negligence; in other words, intentional and unintentional killing is against God’s will. Full stop. Since we believe that God is the source and giver of life, it follows that it’s not our right to end it. But nor is it our duty obstinately to prolong it. That’s where palliative care plays its crucial part.

Michael Wenham trained as a teacher before hearing a call to full-time Christian ministry. For many years was the vicar of three village churches in the Vale of the White Horse, near Oxford, UK.

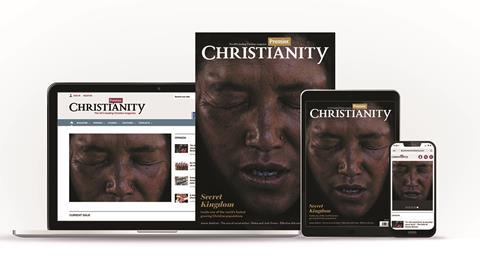

Click here for a free sample copy of Premier Christianity magazine